A reaction against a perceived homogeneity of style has led some intrepid estates – big and small – to turn back the clocks for inspiration and produce wines with a pioneering spirit, writes Matt Walls

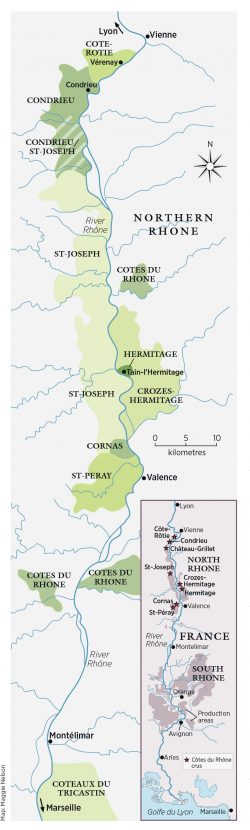

Compared with the draughtsman’s precision of Côte d’Or vineyards, the northern Rhône feels more impressionistic. It might have 2,000 years of history to build on, but in many ways it’s still discovering itself: most of the main appellations still have land to plant on and, compared to other famous names, some of it is relatively affordable. That it never stands still makes the area endlessly fascinating.

Though most producers embrace a more or less classical expression of their terroir, this is still a region where the prospector, the radical and the idealist can carve out a space and a style of their own. Here, you’ll find producers pushing the boundaries by exploring forgotten terroirs, following thought-provoking philosophies, practising unusual techniques and rejuvenating ancient varieties. And for many of them, looking forward means looking back.

Though most producers embrace a more or less classical expression of their terroir, this is still a region where the prospector, the radical and the idealist can carve out a space and a style of their own. Here, you’ll find producers pushing the boundaries by exploring forgotten terroirs, following thought-provoking philosophies, practising unusual techniques and rejuvenating ancient varieties. And for many of them, looking forward means looking back.

St-Joseph: the big players

Though the most radical approaches are found among smaller domaines, the big houses are not standing still. There is an ongoing push for quality, and all eyes are on St-Joseph. This 50km stretch of vineyards runs along the west bank of the Rhône so, unsurprisingly, it varies in quality. But the best sites are easy to spot: jagged granite terraces jutting up from the river like Gaudi cathedrals re-imagined by H R Giger. Just as their potential is obvious, so are the drawbacks: reclaiming these steep vineyards and rebuilding the walls that hold them up requires enormous manpower and investment that only the big houses can afford.

E Guigal

Philippe Guigal says that St-Joseph ‘is decidedly the rising appellation in the northern Rhône… It will gain in fame and note as time goes on.’ One of his most recent St-Joseph acquisitions is the Vignes de L’Hospice, a dizzyingly steep 3.4-hectare vineyard behind the town of Tournon. He has commissioned soil analyses that show that millions of years ago this vineyard was part of the same block of granite that now makes up the Les Bessards lieu-dit over the river in Hermitage. It took eight masons five years to rebuild the walls. But with terroir like that, no wonder he’s banking on it.

Jean-Louis Chave

Jean-Louis Chave believes about 10% of St Joseph has the potential for greatness, and is determined to reveal it. The Rhône flows mostly north to south, but where perpendicular tributaries join the river, they have cut deep into the granite to create southeast-facing terroirs that he describes as ‘grand cru sites’. ‘I’ve been working on this idea for 20 years,’ he says. ‘We have masons doing all this reconstruction, little by little. It takes time… It will take my whole life.’ Currently he blends them to produce a single red St-Joseph, but in the future he hopes to bottle each site separately and produce some white St-Joseph as well.

Delas

Delas has also seen success with its single-vineyard St-Josephs, particularly from St-Epine. It is currently trying a micro-cuvée white version. For winemaker Claire Darnaud-McKerrow, being part of a large group gives her the financial freedom to experiment. ‘On the one hand, you have to be super-modern – we’re doing two million bottles a year,’ she says. ‘On the other hand, we’re doing little one-barrel ferments.’ Having a well-equipped winery affords precise attention to detail; its 2ha Clos Boucher vineyard in Condrieu is split into five blocks that are all picked and vinified separately before blending, to show off the site to its best advantage.

Michel Chapoutier

Having a dynamic pioneer like Michel Chapoutier as president of Inter Rhône (the professional body in charge of promoting the region’s AC wines) no doubt injects energy into the region. He seems in an almost perpetual state of experimentation, whether releasing cuvées in partnership with top chefs such as Anne-Sophie Pic, exploring other regions or countries like Alsace or Australia, or producing new wines closer to home. One new project, soon to be released, is a top-end sparkling St-Péray called La Muse de Wagner, made from 100% Marsanne.

But as the big players continually strive to create higher-quality wines, it’s the smaller ones that have the freedom to really push the boundaries.

The little guys

Eric Texier

Where do you start with former nuclear engineer Eric Texier? How about Opâle, his 7% abv sweet Viognier? Or other whites with eight months’ skin maceration? Not everything he makes is so leftfield. His work redeveloping the forgotten terroirs of Brézème and St-Julien-en-St-Alban has yielded wines that are less extreme in flavour but equally fascinating.

Both are further south than St-Péray, the most southerly of all the northern Rhône crus, with St-Julien-en-St-Alban on the west bank and Brézème on the east. Crucially, they don’t cross the border into the southern Rhône, so the reds are 100% Syrah and Texier uses 100% Roussanne for the whites. He has a minimal intervention approach and farms his estate organically.

Texier first became intrigued by Brézème after reading about its former glory in a book from the 1880s. On visiting, he found just a few hectares left, so set about rebuilding it. His St-Julien-en-St-Alban vineyard is grown on gneiss, while those in Brézème are on a base of clay-limestone, which Texier says gives wines that are ‘more lively, with higher acids – wilder than those on granite or schist’. Both are pushing for appellation status; if you thought you’d seen it all in the northern Rhône, think again.

Aurélien Chatagnier

That some domaines have been established for centuries must be daunting for newcomers. Jean-Louis Chave’s domaine was established in 1481, more than 500 years before Aurélien Chatagnier started his in 2002 aged just 22. For a young winemaker to establish an estate in the northern Rhône and quickly thrive in one appellation is a great achievement. But from renting 1ha of Vin de Pays to working 7.5ha across four of the top appellations in a decade is even more so.

Chatagnier doesn’t come from a winemaking family, but he has been helped by a number of old hands such as Pierre Gaillard. Based in the north of St-Joseph, he produces a Côte-Rôtie, a Condrieu, a Cornas, three St-Josephs and three Vin de Pays, working as much as possible without the use of pesticides or herbicides. Stylistically the wines are drinkable rather than imposing, and each speaks candidly of its origins. Although it has been hard graft, Aurélien proves that it’s still possible for a young newcomer to set up and prosper. This is an estate to watch.

La Ferme des Sept Lunes

Many of the great estates of the northern Rhône started out as polyculture farms, incorporating cows, cereals, fruits and vines, before concentrating solely on wine. Jean Delobre kicked the cows out of the stables to make room for vats, but the other crops remain. Although he admits to being seduced by the esoteric side of biodynamics (‘it makes me feel a bit like a druid’), it was the results in the vineyard and in the finished bottle that convinced him to continue.

The farm is in the village of Bogy near the centre of St-Joseph. It’s been in the family since the 1930s, and since 1997 Delobre has worked the vineyard biodynamically. From 2005, he has operated almost entirely without added sulphur. Sometimes it can bring an oxidative element into play, but Delobre believes that as long as it isn’t too marked, it can bring complexity, particularly with his whites.

He produces two white and two red cuvées of St-Joseph, alongside a still and a sparkling Gamay. Delobre describes making wine without resorting to technological or chemical crutches as a kind of ‘close combat’, which results in wines that are more original and varied. Natural winemakers are relatively rare in this part of France, but Delobre is making wines with a pastoral character that speak of the northern Rhône with remarkable eloquence.

Domaine des Miquettes

Within the northern Rhône, Paul Estève’s chai is unique. At first it appears to be completely empty. But then you notice the circular ceramic mouths poking an inch or so out of the sandy floor. It was during a visit to Georgia that he and his longterm partner Chrystelle were inspired to experiment with clay amphorae buried in the earth. Now they own 26, and use them for the vinification and maturation of the red and orange wines they call Madloba (‘thank you’ in Georgian). The red is made from Syrah and their orange wine is a blend of Marsanne and Viognier; both spend six months on the skins and a further six months maturing in amphorae. He also makes some more conventional red St-Joseph, but doesn’t add sulphur to any of them.

The pair were farm workers before taking over the vines of their family estate in 2003, which is situated near the tiny village of Cheminas, high on the Ardèche plateau. It now amounts to 3ha in St-Joseph and 1ha of Vin de Pays Syrah and Viognier. They have worked organically from the start, and have experimented with biodynamics since 2012. Their wines are fresh, aromatically unrestrained, distinctly tannic and highly unusual.

Domaine Nicolas Gonin

Nicolas Gonin’s estate lies between the Rhône and Savoie. His is one of just four estates in the tiny Vin de Pays Isère-Balmes Dauphinoises, 30km northeast of Côte-Rôtie. His is the only one that works organically, and he devotes himself to the revival of ancient local varieties such as the reds Persan and Mecle, and whites Altesse and Verdesse.

Stylistically, his whites are similar to those of his alpine neighbours, but his reds share common ground with the northernmost reaches of the Rhône, albeit in a leaner style. ‘We harvest just a few days later, the climate is very similar,’ he says. ‘Some of our grapes used to be planted both here and in the northern Rhône.’

Gonin is now working to reintroduce some heirloom grape varieties with a number of Rhône producers, including Pascal Jamet (red varieties Dureza and Durif), Domaine des Amphores and Vignobles Verzier Chante-Perdrix (the red Mornen Noir). Gonin’s wines offer a fascinating insight into how some alternative grapes of the Rhône might once have tasted – and what they might taste like again one day.

Journey of discovery

The northern Rhône may be one of the classic wine regions of France, but it still has the power to surprise. On the one hand, there is an encouraging long-term vision among the big players in their push for quality. On the other, many small estates have the self-belief and courage to really push the boundaries. We could just as easily have included Domaine des Lises and Domaine Melody in Crozes-Hermitage; Guillaume Gilles and Mickaël Bourg in Cornas; Domaine Pichat and Domaine François et Fils in Côte-Rôtie; Domaine du Tunnel in St Péray… the list goes on.

There is a growing sentiment that advances in modern winemaking technology – adopted throughout the Rhône in the early 1990s – did a lot to raise overall quality levels, but also led to a certain homogeneity of style. Increasingly, what it means to be cutting-edge today is to look backwards to history and tradition rather than forwards to new technology, to take inspiration from forgotten terroirs, ancient grape varieties and antique winemaking practices.

Let’s hope these pioneers inspire others to take a walk on the wild side.