Vladimir Kojic has worked in the wine industry for 20 years. He started as a sommelier working for the Cunard cruise line and the Queen Mary 2, before moving to the Soneva Kiri hotel, on a remote island in Thailand. He passed the Court of Master Sommeliers’ Advanced-level qualification in 2012, and is studying for Master Sommelier. He is now head sommelier at star Indian chef Gaggan Anand’s restaurant Gaggan in Bangkok, which opened in late 2019 and is currently at No3 in The World’s 50 Best’s listing of Asia’s 50 Best Restaurants.

The origin of the natural wine movement is usually attributed to a gang of four who were working in Beaujolais in the early 1980s: Marcel Lapierre, Jean Foillard, Jean-Paul Thévenet and Guy Breton. For me, as someone from the Balkans born in 1983, the movement also had important roots in Styria, a small, hilly region in Austria on the border with Slovenia. It has a mosaic of soil types, the most common being a calcareous marl called opok.

When it comes to grapes, white varieties dominate here – Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay and Muskateller among them; for reds, the main varieties are Zweigelt and Blauer Wildbacher, a relative of Blaufränkisch with racy acidity and a fruity robustness.

Instead of talking in general terms about the region itself, I want to introduce you to what I call the Styrian Gang of Four: Sepp Muster, Ewald Tscheppe, Andreas Tscheppe and Franz Strohmeier. This unofficial grouping, brought together for the purposes of this article, is important. Its members have helped to transform the picture of Austrian winemaking and their efforts have led to an explosion in numbers of low-intervention growers, not just in Styria but across the whole country. The four are best friends (and sometimes family), working with similar soil types, climates and philosophies, but when it comes to the wine they produce, there are four different worlds out there.

Sepp Muster

Weingut Maria & Sepp Muster

From a traditional winemaking family, Sepp Muster’s views on agriculture, winemaking – and life – changed drastically after a car accident. He turned to biodynamic practices in the vineyard and a minimal-intervention approach in the cellar – or, as he says, ‘not doing much, and letting things happen’. I have often served his white wines (50/50 blends of Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc) blind and the most common guess I get back is top-class Jura Chardonnay, where a reductive character can show in youth, yielding over time to a spectrum of complexity. Turning to red, Zweigelt is the only grape he works with, and in his older vintages I find many similarities with the top wines of the Rhône valley.

Try: Sgaminegg, a blend of Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay. In its youth, there’s always a strong presence of reduction, which I compare to the smell of curry leaf. But you’ll also find stone, apple and peach aromas, insane acidity and a long finish.

Ewald Tscheppe

Weingut Werlitsch

Ewald Tscheppe’s vines are planted on a small hill next to his house, and he has established his own, Burgundian-style classification system. Grapes from the base of the hill go into Ex Vero I, those from the middle go into Ex Vero II, and fruit from the hilltop goes into Ex Vero III, his equivalent of a Burgundy grand cru. The wines are a blend of Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc, never see new oak and have an intense balance of acidity and minerality – and for me, they are everything the best Burgundies ought to be.

Try: Ex Vero III 2013, another Chardonnay- Sauvignon Blanc blend. Precision and freedom, in a single bottle. (2020, £66-£69 Newcomer, Oranj)

Andreas Tscheppe

Andreas & Elisabeth Tscheppe

@weingut_andreas_tscheppe

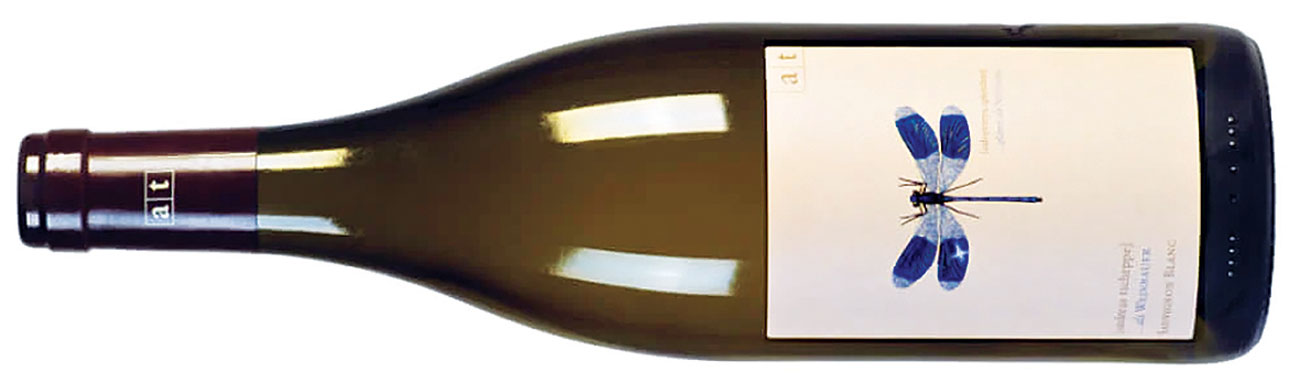

Ewald Tscheppe’s brother Andreas is also a winemaker, located just next door to him, and affectionately called the Wizard of the Hill by his friends. Andreas’ wines are named after amphibians and insects, such as Salamander, Stagbeetle, Dragonfly… all the living creatures that he considers friends. These are clean, precise wines, but are very different to those made by his brother.

Try: Blau Libelle 2017, a Sauvignon Blanc unlike any other: green olive texture but with aromatic scents, high acidity and a very long finish. (2022, £50-£55 Cellar Next Door, Hedonism, Les Caves de Pyrene)

Franz Strohmeier

Franz Strohmeier

In my eyes, Franz was never a winemaker, but a philosopher who transferred his philosophy into the bottles. These aren’t wines that you can just grab from the shelf and open – you need to dedicate time to tasting them with your full attention, trying to understand what they aim to do. Once you’re in tune with that, whatever you open of his will be pure magic. His wine labels all display the same words in German: Trauben, Liebe und Zeit (‘Grape, Love and Time’). Grapes are the raw material; you can’t make good-quality wine without love; and in the end, the wines need time in bottle to show at their best. That’s Franz’s philosophy in a nutshell – in the end it’s pretty simple.

Try: Wine der Stille No6 (NV, US$89 The Cellar d’Or), a blend of Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Muskateller and Weissburgunder (Pinot Blanc). As if reading a book, this evolved with time in the glass. It started out with aromas of Pecorino cheese, then was reminiscent of ripe blood oranges, and ended up with a Japanese umeshu plum liqueur character, with some sweetness.