The broad spectrum of flavours and aromas that toasted new oak can impart to wine is more than familiar, from vanilla and caramel to rich mocha and baking spices. But costing as much as £700 a piece, it would be hard to justify purchasing new oak barrels for their flavour alone. So what exactly is the role these expensive vessels play?

What is the role of oak barrels?

This article is an edited version of William Kelley’s feature on ‘the role of the barrel’. Subscribe to Decanter magazine here to read the full piece in the November 2016 issue.

Oak fermentation for white wines

Many of the world’s greatest white wines ferment and mature in oak casks. It’s labour intensive, but for many winemakers, the benefits amply justify the trouble.

The barrels establish intimate contact between the wine and the yeasts that carry out fermentation. As sugar is transformed into alcohol, those yeasts die, sinking to the bottom of the barrel to form a layer of lees.

‘They scavenge oxygen, protecting the wine through fermentation and maturation,’ explains Pierre Boisson, rising star of Meursault.

As yeast cells in the lees break down – a process known as autolysis – they release desirable substances into the wine, including amino acids and polysaccharides, which improve flavour and texture, as well as glutathione, an important antioxidant.

The result? ‘Barrel fermentation produces richer, more ageworthy Champagnes,’ insists Julie Cavil, Krug’s winemaker.

Jean-François Coche-Dury, in Burgundy, agrees, believing that intimate contact between wine and lees is critical to quality: ‘The wines acquire strength and structure, muscles and sinew,’ he says, ‘which allow them to age for a long time.’

The art of élevage

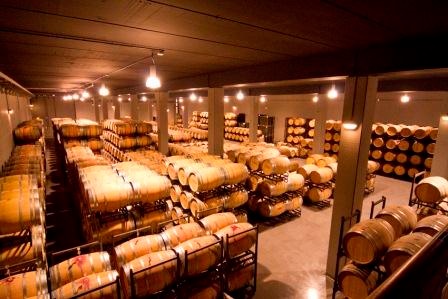

In red winemaking, oak barrels are central to what the French call élevage: the art of ‘raising’ or maturing a wine to ready it for the moment of bottling.

The key to élevage resides in a wine’s relationship with oxygen; exposure to just the right amount promotes reactions that intensify colour and soften hard tannins.

‘The objective of a traditional élevage is to work with oxygen to civilise and refine a wine’s structure,’ explains François Mitjavile, winemaker-proprietor of St-Emilion’s Tertre-Rôteboeuf.

‘At the same time, we seek to open and develop its aromatics’.

If the winemaker deems it necessary, the degree of oxygenation can be increased by decanting the wine from one barrel to another – known as racking.

Building barrels at Bodegas López de Heredia, Rioja.

Choosing a cooperage

Differences in coopers’ house styles are a particularly important aspect of barrels, and each winemaker has his or her favourites. Some prefer to work with just one cooper, but others work with several – something commonly seen in Bordeaux.

‘The magic marriage is usually not achieved with just one cooper,’ said Château Angludet’s winemaker Benjamin Sichel.

‘You need the blend of multiple signatures, all slightly different, to reach it.’

In Napa Valley, Aron Weinkauf of Spottswoode takes a similar approach, drawing on a number of coopers including Darnajou, Nadalié, St Martin, Sylvain, Taransaud and Vicard.

One of the defining features of each cooper’s ‘house style’ is its proprietary toasting process, which dramatically alters the wood’s physical and chemical composition.

More heavily toasted barrels lend a wine sweetness and amplitude, as well as bringing rich, roasted aromas of coffee and caramel. By contrast, lighter toast levels bring aromas of vanilla and fresh wood to the fore.

Cooperage at Louis Jadot, Burgundy.

Counting the grain

Even more fundamental is the choice between European and American oak.

In European forests, Quercus sessilis and Quercus robur predominate; in North America, it’s Quercus alba, a species with much less soluble tannin than its European siblings, but higher concentrations of aromatic substances – in particular, creamy oak lactones.

The distinctive aromas of vanilla and coconut derived from American oak are commonly encountered in the wines of Rioja and Australia, but find comparatively few admirers elsewhere.

More subtle than the differences between American and French oak are differences between the forests of France.

‘Limousin oak is wide-grained and contains very few aromatic lactones, but a lot of tannin, which extracts rather rapidly,’ explains Camille Gauthier, one of France’s most respected experts on barrel staves.

‘Allier wood is tighter and contains, for example, more eugenol, which brings the scent of cloves.’

The complexities are endless: a tree that grows next to a forest track, for example, will grow at a faster rate and produce wider grained wood than other trees because of its easier access to sunlight.

Old or new?

A further permutation is the question of what proportion of new oak to use; a choice just as decisive for red wine as for white.

The first growths of Bordeaux and many of the great estates of Burgundy often use brand-new barrels for each vintage, though other winemakers, such as Volnay’s Frédéric Lafarge, avoid it entirely.

‘I like new oak for the precision it can bring’, says Jeremy Seysses of Domaine Dujac. ‘But I like the oak to provide an underpinning, rather than to be a dominant feature.’

Seysses notes that ‘using neutral, previously used barrels marks the wine too, but in different ways’.

And it’s also true that some wines are able effortlessly to assimilate even copious quantities of new oak.

Edited for Decanter.com by Ellie Douglas.

Related content:

Anson on Thursday: Oak ageing holds key to wine sweetness

Rioja winemaker swaps oak for chestnut

Rioja producer Oscar Tobia is experimenting with alternatives to oak barrels for ageing and plans to release a blended white

Acidity and wine age – ask Decanter

Does acidity remain constant or can it alter over time? Stephen Skelton MW explains the relationship between acidity and wine