Wine writings are full of discussions about different grapevine varieties, often with mentions of the soils they are growing in. But usually ignored is the thing that links the two together – the vine rootstock. OK, it’s pretty much out of sight in a vineyard and lacks glamour, but it’s the engine of vine growth and is crucial to a vine’s defences against soil predators. Rootstocks influence how grapes ripen and hence, indirectly, wine taste. So why don’t we hear more of them?

The concept of vine rootstocks came to the fore during the phylloxera crisis, when Europe’s defenceless grapevines were saved by grafting them onto phylloxera-resistant North American roots. The history is well documented, though the pivotal role of vineyard soils much less so. Here’s the story…

Of roots and soils

Early attempts at grafting the fruiting part of Vitis vinifera, the European grapevine which produces superior tasting wines, onto a different rootstock used Vitis riparia. Its roots grafted well and showed good resistance to America’s indigenous vine louse. As its name indicates – riparia meaning to do with rivers – it flourishes on moist, fertile riverbanks. But this presented a problem in France. Almost half of the country is underlain by limestone and many of the vineyard regions are dry, stony and calcareous (ie, dominated by calcium carbonate). And this is especially true of such classic areas as Champagne, Burgundy and the Cognac-producing Charente. Riparia didn’t do at all well in these alkaline soils.

So rootstocks of Vitis rupestris were tried and – rupestris meaning rock-living – these fared better in stony soils. But again not if they were calcareous. The problem is that while in America these vines had evolved alongside the indigenous phylloxera bug and hence had developed resistance to it, they had done so in rather acid soils. Might there be an American wild vine living happily in alkaline, calcareous soils? Beleaguered French grape growers urged action.

A young man on a mission

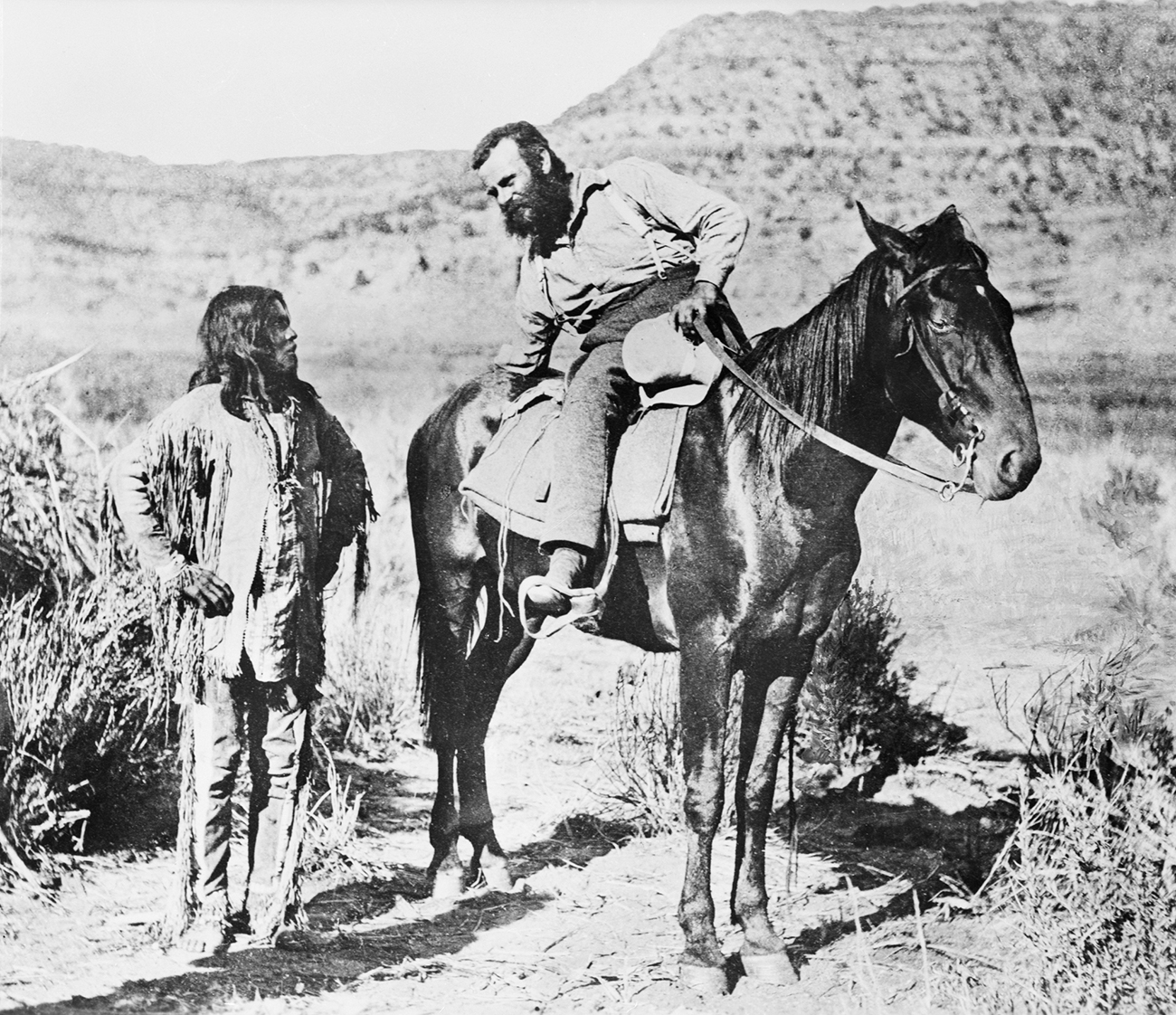

So it was that in March 1887 Pierre Viala was appointed to search for this viticultural holy grail. Just three months later he was in New York. Viala was a young professor in the Montpellier School of Agriculture, a trained botanist and from a grape-growing family, so he could deal with vines but he didn’t know much about rocks and soils.

Thus his first task in the US was to seek geological advice. John Wesley Powell – once a Civil War major in the Union Army (losing an arm at the Battle of Shiloh as he raised it to signal to his troops) and first surveyor of the Grand Canyon – was Director of the newly founded US Geological Survey. In Washington, Powell showed the relevant geological map to Viala. He explained that there was plenty of limestone to hand in Maryland, Virginia and the states around, and out west there was an immense area of calcareous rocks formed in the same geological period (Cretaceous) as those in the Charente and Champagne.

So Viala set out into the land of Scuppernong and Mustang grapes. But only then did he realise that the limestone bedrock is hidden beneath a thick covering of loose material brought in over the millennia by ice sheets, wind and rivers. He wrote: ‘If there are limestone formations in America, they are almost always covered by layers of humus of such thickness that the influence of the limestone subsoil can in no way be felt’. And wherever he did find a bit of limestone at the surface, any local vines were invariably struggling. ‘Not one of the varieties of the North and the East has value for calcareous and marly soils’, he concluded.

Go west, young man

Viala was sent extra funding in order to continue further westwards, even into ‘Indian Territory’. But there he still found the bedrock to be largely covered by thick ‘black earth of an extreme fertility’. So he decided to go all the way to the west coast, across ‘the most arid countries that you can imagine’. There, however, he only found imported European vines, already decimated by phylloxera ‒ and no limestone.

Viala was sending frequent reports back to France; such was the public interest that they were published in the magazine Le Progrès Agricultural. They were read avidly by growers even though they contained very little optimism. But suddenly one account signalled a change. Highly cryptically, it reported: ‘I have interesting facts, but I cannot violate things by letting you know these official secrets.’ The magazine was inundated with enquiries: What had he found? Is he going to save our farms? What Viala had found was the expertise of Thomas Volney Munson.

French wine saved by Texas?

The little Texas town of Denison, north of Dallas, would seem an unlikely twinning (sister town) with the celebrated French city of Cognac. But there is a connection, and it comes via rootstocks. Illinois-born Munson was an indefatigable cataloguer of American vines and was now living in Denison. Viala travelled there to meet Munson, and the two immediately hit it off. (Later Munson named one of his daughters Viala!) Munson not only understood vines but he knew their habitats and, crucially, the soils they grew in. And yes, he knew exactly where vines were thriving on rocky limestone.

Thus Viala rode down to Texas Hill Country, to a place just west of Belton called Dog Ridge. It was ‘horribly dry land, with Indians on it’ but the soils were remarkably similar to those of Charente: alkaline and chalky. And ‘in them grew abundant vines’. Viala found the particular species that Munson had recommended ‒ Vitis berlandieri ‒ and soon 15 wagon loads of cuttings were taken away and loaded onto three ships bound for southern France. The holy grail was on its way!

It’s in the breeding

Every gardener knows that you can stick cuttings from some plants into the ground and they promptly take root, while others just sit there. Unfortunately, berlandieri is in the latter camp. In fact, the species was known in France well before Viala’s adventure, its name coming from the Swiss-Mexican naturalist Jean-Louis Berlandier who had sent samples nearly 50 years earlier. They were seen back then not to root well and had been paid little attention. But now that Viala had highlighted their affinity for chalky calcareous soils berlandieri was suddenly in the spotlight.

Most species have within them varieties with differing characteristics, so one strategy was to isolate those varieties of berlandieri that showed a better propensity for rooting and then enhance that further through continuing selections from successive offspring. Another approach was to cross berlandieri with another species that does root well, and this is exactly how 41B came about. (Wouldn’t rootstocks be less ignored if they had catchier names?) This rootstock was a cross of the vinifera Chasselas with a suitable strain of berlandieri, and the result managed to tick enough of the right boxes. It was to prove the saviour of the Charente vineyards, hence the Denison/Cognac twinning. It is still used today in more than 80% of the vines in Champagne.

After a period of intense breeding of rootstocks suitable for different conditions, about a score of them became the most widely practicable and popular. And apart from a handful of later variations they are essentially the same rootstocks that are available to the world’s growers today. Meanwhile, however, nature has moved on.

The gathering storm

Environmental conditions shift, especially in these days of climate change. A rootstock that used to cope with some aridity, for example, might now be inadequate for today’s increasingly intense droughts and soil salinities. Then there’s the pests. There’s a range of vine predators and pathogens in soils, and these are constantly changing. As for phylloxera itself, putting aside its quite bizarre sex-life, the louse has complex and variable lifestyles that equip it well to adapt to new conditions. It’s evolving.

For example, eight different ‘biotypes’ together with nearly 100 genetically distinct ‘superclones’ of phylloxera are now known. Yet on the other hand, about 99% of all vine rootstocks currently used commercially are still derived from some combination of vinifera, riparia, rupestris and berlandieri, mostly coming from the same few varieties. Consequently it’s a very limited gene pool, which makes vine roots very vulnerable to their evolving adversaries. In other words, to caricature the situation just slightly, vines are facing an array of constantly evolving enemies while relying on defences from more than a century ago.

Looking for answers

Some vine scientists think an answer may lie in the multifarious wild vine species that extend right across Asia. They may not have experienced phylloxera but some might just have a property that gives them resistance. Other scientists feel that trying to wring further tweaks from rootstock interbreeding should be abandoned in favour of modern methodologies. The obvious and potentially most powerful one is genetic modification (GM). Of course, even that very name strikes horror into many across the vine industry. But then, to many grape growers once upon a time, so did the idea of adulterating heritage French vines with American roots…