- The fact that a wine has been grown in the Bordeaux area and conforms to certain standards does not necessarily guarantee quality.

- Model vineyards have been planted in the different areas as a life-size demonstration of how a vineyard should be managed for the production of top quality grapes.

- The headquarters of the Syndicat des Bordeaux and Bordeaux Supérieur has evolved from a meeting place for wine growers into a consumer initiation and training centre.

- The variety of styles and individual characteristics of AC Bordeaux or Bordeaux Supérieur Petits Châteaux are making them increasingly popular.

Behind every bottle of Bordeaux or Bordeaux Supérieur there is a man or, often enough these days, a woman. The wine reflects the vintner’s personality by the decisions he or she has to take,’ says Jean-Louis Roumage, president of the Syndicat des Bordeaux & Bordeaux Supérieur. Roumage, himself a vintner, owns Château Lestrille, a 33 hectare (ha) vineyard in the Entre-Deux-Mers. ‘These are wines with the human element, the work of a craftsman, not a faceless conglomerate.’ This human reality has made them more and more popular. In 1972, one million hectolitres of Bordeaux and Bordeaux Supérieur appellation wines, red, white and rosé, was being sold. Today the quantity has tripled and represents 55% of production from the overall Bordeaux wine area.

Bordeaux & Bordeaux Supérieur

There are roughly 7,000 members of the Bordeaux & Bordeaux Supérieur Syndicate cultivating a total 60,000ha of vineyard, dotted throughout the region. At one time white wine was the main production, but today roughly 50,000ha are planted to red (40,000 Bordeaux, 10,000 Bordeaux Supérieur) and only 10,000 to white grape varieties. However, the vast majority of Bordeaux appellation vineyards are concentrated on the east of the River Garonne and the Gironde Estuary, the ‘Right Bank’: Entre-Deux-Mers 75%, the Bourg/Blaye area 6.5%, the Libournais 16.5%. Although a generic Bordeaux will not have the pretensions of a Médoc or Graves, or one with an even more restricted ‘communal’ appellation like Pauillac or Margaux, Pomerol or Sainte-Croix-du-Mont, each Bordeaux reflects the style of wine relative to its origin – its terroir. Of these 7,000 growers, 3,000 prefer not to invest in their own winemaking facilities and truck their grapes to one of the 42 cooperatives, which either use them to produce their own generic brand or they may vinify, age and bottle it separately under the château label. The other 4,000 make their own wine and about 20% of them bottle and market their own product.

The Bordeaux Supérieur appellation is produced under stricter conditions (older vines, lower yield, minimum 12 months ageing) and significantly 77% are château-bottled. However, the bulk of Bordeaux appellation wines, around 80%, is sold to one of 400 négociants who use it to blend their own brands with names like N° 1 de Dourthe, Mouton Cadet, Ginestet, Signatures, La Cour Pavillon, Yvecourt Premius, and so on. However, the fact that a wine has been grown in the Bordeaux area and conforms to certain standards (grape varieties, pruning system, maximum yield, etc) does not necessarily guarantee quality. Consequently in 1967, the Syndicat des Bordeaux & Bordeaux Supérieur was the first to institute an analysis and tasting control – known as the agrément (approval) – in spring following the harvest, to ensure that wines laying claim to the Bordeaux appellation were worthy of the title.

Wines not up to standard are given a second chance in September, delaying release, but if not approved the second time, they won’t get the appellation and have to be sold as Table Wines, a big financial loss. Because of this, tasting committees have sometimes been accused of lowering standards and certain négociants would like to see a new, intermediate category created, a vin de pays for Bordeaux wines. Such a suggestion is anathema to the Bordeaux Wine Syndicate because it would create a rival category within the Bordeaux appellation area. ‘Our objective is to raise quality standards,’ says Roumage. ‘Not give vintners an excuse to make lower quality wines.’ Even so, there can still be many a slip twixt the vat and the consumer’s lip. Once the wine has been approved, it has to be aged, blended and bottled before being released, and latterly there has been an outcry from distributors against the fall-off in quality of the final product, especially in comparison with wines from other parts of the world. To counter this apparent quality shortfall, the Bordeaux Wine Trade Council (CIVB) recently set up a control further down the line. The measures concern not just generic Bordeaux but all appellations in the Bordeaux wine-area. Jean-Louis Trocard, previously president of the Bordeaux & Bordeaux Supérieur Syndicate, now president of the CIVB, warns vintners: ‘The appellation, which is a right, also involves a duty.’

For nearly 18 months now, the CIVB, together with the Institut National des Appellations d’Origine (INAO), has been controlling Bordeaux wine at the consumer stage. Specialised companies, working to a given sampling plan, select specified wines in the different markets and return them under seal for examination. A three-man tasting panel (négociant, broker, vintner) checks out the sample. If a wine is not considered up to the standard required for the given appellation, a warning letter is sent by registered post to the person responsible: viz, the name of the bottler on the label. This name, the ‘signature’, represents the person who has, in substance, declared the wine worthy of its appellation. For the time being, the control committee has not yet gone beyond an official warning, like a yellow card in football, on the basis that to err is human.

But the reputation of Bordeaux wines is at stake. The Syndicat des Bordeaux & Bordeaux Supérieur has taken the slur implicit in this action very seriously and reiterated its dual objective: to promote better quality and generalise technique. Techniques are being constantly improved, but technique alone cannot make good wine from poor material. As president of the Syndicat, Roumage stated his mission very clearly: ‘Our essential role is to motivate our growers to produce better quality grapes.’ As an aid and encouragement to vintners and to promote this prime objective, model vineyards have been planted in the different areas as a life-size demonstration of how a vineyard should be managed for the production of top quality grapes. Better quality commands better prices and wine lovers are ready to pay that little extra. Patrick Carteyron is sécretaire général of the Syndicat and himself a vintner working Château Pénin, a 31ha vineyard in the Entre-Deux-Mers region. ‘Petits Châteaux are inexpensive anyway, so that a price-hike will be negligible,’ he pointed out. In recent years the tendency has been to produce a special cuvée, which enables a conscientious vintner to ask a higher price than regular Bordeaux and apparently consumers are eager to pay the extra. ’14 years ago, I bought 10 new barrels to experiment with a special cuvée for more discerning customers,’ says Carteyron. ‘It has been a phenomenal success. Today, I use 200 new barrels and renew them by one third each year. My customers are delighted to pay a little more for a well-made, oak-aged wine, showing that price is not the essential factor, but quality.’

The headquarters

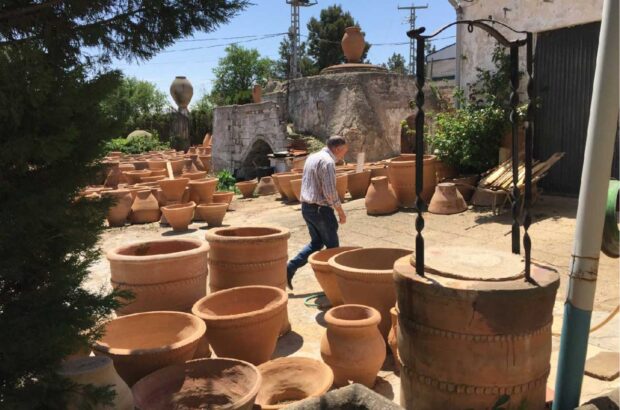

Significantly, the headquarters of the Syndicat des Bordeaux and Bordeaux Supérieur, built in 1979 along the highway halfway between Bordeaux and Libourne, was named La Maison de la Qualité. This is where the agrément tastings take place every spring, a vast operation involving between 10–12,000 individual samples selected from the vintners’ vats. A special ultra-modern tasting room is equipped for the purpose and has been opened to the general public. Although the Syndicat’s main objective is improving and controlling the quality of the wines made by its members, it also exercises an important promotional function. To that end, La Maison de la Qualité has evolved from a meeting place for wine growers into a consumer initiation and training centre.

Welcomed individually, or by group, visitors are first taken through a permanent exhibition, called ‘Planète Bordeaux’, a life-size demonstration of the vine growing and winemaking processes in six entertaining and informative stages, with a choice of commentary in English, French or German. The itinerary leads directly to the ‘Senses and Colours’ console, an aid to awakening sensitivity to different aromas and tastes. A small demonstration vineyard has been planted outside the centre with a thousand vines featuring all the different Bordeaux grapes: Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Sémillon and so on. Visitors may then want to follow one of the specially prepared auto-guided tours, called vitinéraires, winding along various routes through the Bordeaux vineyards with all their different styles and grape varieties. It is this subtle blend of different varieties that gives Bordeaux its nuances and the Syndicat des Bordeaux & Bordeaux Supérieur is fiercely opposed to any attempt to produce varietal wines in Bordeaux. ‘We must, above all, cultivate our specificity which is a vin d’assemblage and not a vin de cépage (varietal wine),’ Roumage states categorically. ‘A straightforward Bordeaux well-made will be more than competitive with a wine from anywhere else at an equivalent price.’

The modest prices of these wines make them an ideal introduction for the inquisitive wine novice. In addition, they represent the whole range of Bordeaux wines across eight different appellations: red and dry white, both regular and Supérieur, rosé and clairet (the famous ‘claret’), sparkling Crémant and a brandy called Fine de Bordeaux. With the backlash against worldwide standardisation and the levelling of taste, the variety of styles and individual characteristics of these AC Bordeaux or Bordeaux Supérieur Petits Châteaux are making them increasingly popular. Overall, quality is improving and, properly selected, they can be unbeatable value.