Right Bank popularity has pushed prices up in neighbouring appellations, so investors have turned their beady eyes to Côtes de Castillon. JAMES LAWTHER MW reports.

It’s gold rush time in the Côtes de Castillon but the precious commodity is land. With prices per hectare (ha) soaring into millions of francs in neighbouring Saint-Emilion, prospectors have been seduced by the attractive nature of affairs in Castillon. ‘There’s lots of good but under-exploited terroir which can be turned around,’ says Stéphane Derenoncourt, consultant winemaker to several Right Bank properties and owner of the tiny 4ha Domaine de l’A in the Côtes de Castillon.Over the last couple of years a steady flow of like-minded heavyweights has arrived on the scene. In 1998, Stephan von Neipperg of Canon-la-Gaffelière and La Mondotte fame purchased the 30ha Château d’Aiguilhe, complete with the ruins of a 13th-century château.

Rising stars

Hard on his heels were Gérard Perse, owner of premier grand cru classé Château Pavie, and Alain Raynaud of rising star Quinault l’Enclos, who jointly acquired Château Clos l’Eglise. Dr Reynaud is now about to add Château de Laussac to his stable, while another with pen poised over contract is Gérard Bécot of Saint-Emilion first growth Château Beau-Séjour Bécot, while oenologist Christian Veyry, an associate of Michel Rolland, has quietly established Château Veyry. The increase in land prices has left the locals agitated, but for once the spotlight is on the Côtes de Castillon.The appellation takes its name from the sleepy riverside town of Castillon-la-Bataille, scene of the battle in 1453 which marked the end of the Hundred Years War and English rule in Aquitaine. Until the 1930s, the wines from this region were sold under the label Saint-Emilionnais or Près Saint-Emilion. They then took the denomination Bordeaux Côtes de Castillon before acquiring the independent status of Côtes de Castillon in 1989.There are now 2,945ha under production (1999 figures) in a zone bounded by the Dordogne River to the south, Saint-Emilion to the west, Saint-Emilion satellites to the north and the Dordogne département to the east.

Saint-Emilion

In fact, the region is a continuation of the Saint-Emilion hill-slopes and has a similar profile to its more august neighbour. Around 30% of the vineyards are on the Dordogne’s silty plain, the rest on the limestone-clay slopes and plateau behind. Here the land twists and turns around a number of small hills and valleys, rising to 117m at Saint-Philippe-d’Aiguilhe. Exposure is a major factor with the harvest generally a week behind Saint-Emilion. The cool, calcareous soils make Merlot the preferred variety to the tune of 70%, with a complement of Cabernet Franc and a little Cabernet Sauvignon. The simplest wines tend towards a briary fruitiness, while the better examples are rich and full with a firm, fresh finish.

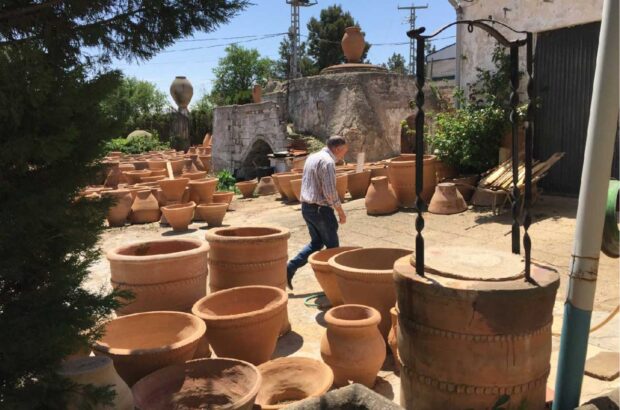

The impact of the nouveaux arrivés has been rapid, with a combination of finance and expertise providing overnight change at their respective estates. Stephan von Neipperg is lavishing as much attention on Château d’Aiguilhe as he does on his grands crus classés in Saint-Emilion. Part of the vineyard has been replanted, vines replaced, pruning and vineyard management improved and hand harvesting into small plastic baskets introduced. The percentage of new oak barrels has been increased (80% for the 1999) and a new circular vinification cellar is planned for 2002. The two opening vintages under the new regime, 1999 and 2000, show beautiful fruit character, the 1999 with a firmer, squarer structure than the 2000, which has more finesse.Much the same turnaround can be seen at Château Clos l’Eglise. ‘We want to show that by applying the same savoir-faire and investment used in the Saint-Emilion grands crus we can produce great wines in the Côtes de Castillon,’ says Alain Raynaud. As well as buying 17ha Clos l’Eglise, he and Gérard Perse purchased the 40ha Château Moulin Rouge, since renamed Château Sainte-Colombe. The politics of management and winemaking vary for each. Sainte-Colombe is higher yielding (50 hectolitres per hectare) and vinified to preserve the fruit character, while Clos l’Eglise has all the care of a top growth: green harvesting and deleafing in the vineyard, hand harvesting, severe selection, long post-fermentation maceration, lees stirring for four months and 100% new oak. The 1999 is rich and sophisticated and would not be out of place in a line-up of Saint-Emilion grands crus classés.

At Domaine de l’A, Stéphane Derenoncourt indulges in the experimentation he is rarely allowed at his consultancies, notably a biodynamic culture for the vineyard and allowing malolactic fermentation to happen in its own good time. The vineyard and quality of fruit are his two obsessions. ‘There are two things that have to be carefully managed in Côtes de Castillon, the high acidity and robust tannins,’ he explains. The ripeness of fruit can help round these out.’ Another newly acquired property, 8ha Château Pervenche Puy Arnaud, is also making great strides on his advice, and owner Thierry Valette eventually plans to embrace biodynamic viticulture. The publicity surrounding the Côtes de Castillon’s new arrivals has tended to obscure the fact that a group of longer-term producers and estates have also made progress in the last few years. The means may have been more limited but these represent the real value for money in the appellation. Among these are Château de Belcier, owned since 1986 by the MACIF insurance company, Château Robin (my pick in a blind tasting of 30 Côtes de Castillon from the 1998 vintage), Château Côte Montpezat, Château La Clarière Laithwaite (owned by Tony Laithwaite of Direct Wines), Château Lapeyronie, Régis Moro of Vieux Château Champ de Mars and Catherine Papon-Nouvel of Château Peyrou. Papon-Nouvel bought her 5ha estate in 1989 and has steadily made improvements at the property, which lies on clay close to the border with Saint-Emilion. The cellars have been renovated, the new oak percentage increased and since 1998 there has been more control of yields from the 40–60 year-old vines, a return to hand harvesting and a more ‘organic’ approach. The 1998, vinified with natural yeasts, has brilliant colour and succulent fruit but a slightly coarse oak overlay. ‘I still have to work the quality of oak,’ she freely admits.

Régis Moro

Régis Moro is one of the leading producers in the Côtes de Castillon. His Vieux Château Champ de Mars, produced from 90% Merlot, is generous and gourmand, like the man himself. The 17ha vineyard is located on the limestone plateau and contains a not insignificant percentage of old vines ranging in age from 40 to 100 years. Yields are held at 45 hl/ha (the appellation limit in 1999 was 60.8) and modern techniques such as microbullage and lees stirring have been embraced. The 1999 vintage sees the release of Cuvée Joanna, produced from grapes from a percentage of the older vines vinified in new oak vats and aged in new oak barrels.Driving around the pleasing Côtes de Castillon countryside it’s clear that there is still room for improvement. Vine densities need to increase and parcels of old, badly cultivated vines must be grubbed up and more investment is needed in the cellars, but progress is being made. The percentage of bottled wines as opposed to bulk has moved from 30% in 1989 to 60% in 2000, of which 40% is bottled and commercialised at the domaine, while prices have risen sufficiently to boost investment. The appellation is advancing into the modern era and the arrival of new producers and a younger generation can only speed this up.

A personal selection

From the 1998 vintage: Belcier, La Clarière Laithwaite, La Grande Maye, Perreau Bel Air, Peyrou, Robin, Rocher Lideyre, Roque le Mayne, Seigneur de Gameau, Vieux Château Champs de Mars

Côtes de Castillon’s new stars: Aiguilhe, Clos l’Eglise, Domaine de l’A, Le Pin de Belcier, Veyry, Vieux Château Champs de Mars Cuvée Joanna