- Campania is a playground dominated by a volcano, a place of archeological pilgrimage

- It was the first part of Italy colonised by the Greeks and it was where they planted their grapes.

- It is an ancient vineyard where the vines are still trained on pergolas.

- One of the region’s greatest treasures is its wealth of quality indigenous varieties.

- Winemakers are now looking radically at singular grape varieties.

- Campania has three high-quality, flavoursome white grapes.

There are many different Campanias. The extraordinary craggy beauty of the Amalfi coast, the Dantean insanity that is Naples, the eerie calm of Pompeii, the island getaways of Ischia and Capri. It’s a playground dominated by a volcano, a place of archeological pilgrimage, home of legends, the start of the south. Wine, for once in Italy, doesn’t take centre stage. To find the best Campania has, you have to travel inland to the area of Irpinia, sheltering in the foothills of the Apennines. ‘Irpinia is part of Campania,’ says Vincenzo Ercolino, head of the region’s top producer, Feudi di San Gregorio. ‘The people aren’t Neapolitan in character, they’re mountain people, individualistic.’ He then launches into an explanation of how local viticulture was influenced by the Greeks and Etruscans. Now, it’s not every day that you get a 3,000-year perspective in answer to a simple question, but Ercolino’s enthusiastic recounting of his region’s history is repeated by every other winemaker you meet.

Campania, you soon realise, is burdened by history. It’s where the famed Roman wine Falernum came from (a fact which prompted the establishing of Villa Matilde); the ominous presence of Vesuvius is everywhere, its legacy can be seen in the streets of Pompeii, or in the soil of the vineyards. The past is strangely alive.

This wasn’t just the first part of Italy to be colonised by the Greeks but, by extension, the first place where they planted their grapes – the names of Greco and Aglianico are evidence of this – and was the first part of Italy where pergolas were (mostly) abandoned in preference to the Greek system of bush training. You get the feeling that little has changed since then, that the region’s too-potent past has hampered rather than helped winemakers over the centuries.

It’s a point that Ercolino is only too aware of: ‘When we started Feudi di San Gregorio we found that though we were working in today’s world, things hadn’t changed from Roman times. The tradition was for bitter wines, but the world wanted soft. We have had to find a new mentality, new ways to work within the tradition.’ The process of change may not be as speedy as a Neapolitan driver, but is rapid compared to the centuries of atrophy. It’s a welcome change in attitude in a region where, until recently, only one firm appeared willing to participate in the Italian wine renaissance.

That firm, Mastroberardino, is currently recovering from a family split in which one branch took the winery and the family name, while the other took the vineyards – all 120 hectares (ha) of them – and set up in a new winery under the name Terredora di Paolo/PLD. ‘Mastroberardino had become a brand,’ claims Lucio Mastroberardino, PLD’s winemaker. ‘I want to go back to the way it was and make innovative wines. We want to be producers, not marketeers.’ It’s true that Mastroberardino had taken its eye off the ball and the firm is now in the awkward position of not only having to buy in all its grapes but rebuild its reputation. The positive side is that, while the reds are still off the pace, the 1997 whites show a definite return to form.

As it stands, both branches of the Mastroberardinos and go-ahead firms like di Meo have their work cut out to catch Feudi di San Gregorio. Although this family firm was only established in 1989 it’s risen from new kid on the block to being head and shoulders above the competition in Irpinia. In Campania, only Villa Matilde can rival it.

That’s Campania for you. Though vines are widely planted, the real jewels are few and far between. Feudi, PLD, di Meo and Mastroberardino in the cool hills of Irpinia, Villa Matilde, Mustilli and Moio in the north and, on Ischia, Casa d’Ambra. All are linked by a willingness not to accept Campania’s heritage, but are asking questions about the tradition; rejecting some aspects, embracing others.

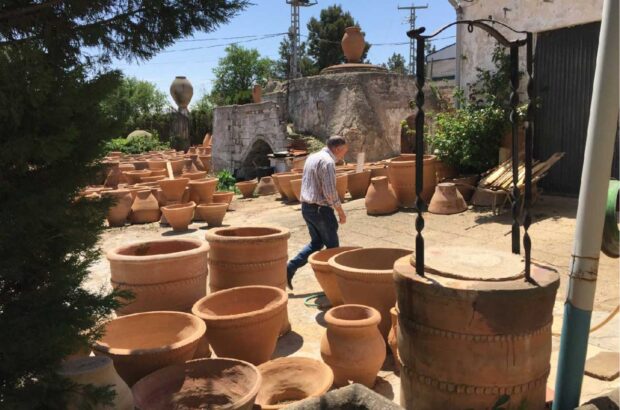

These investigations have produced some remarkable discoveries such as revealing the secrets of an ancient vineyard on the outskirts of Taurasi where the vines are still trained on pergolas. Some of these thick-trunked trees were planted 180 years ago and not only contain various clones of Aglianico but, bizarrely, some ancient Syrah. Cuttings are now being taken from these venerable vines, giving winemakers access to a hidden wealth of quality clonal material. It’s all part of an attempt not just to improve the wines, but to tap into the mysteries of Campania’s forgotten heritage.

One of the region’s greatest treasures is its wealth of quality indigenous varieties. At the University of Naples, research scientist Luigi Moio is trying to crack their secrets. Moio, whose father makes a densely structured Primitivo in the north of the region, is investigating the chemistry and technology of aroma, singling out the volatile compounds responsible for the key aromas in wine. He then can create ‘aromagrams’ for each variety, their aromatic fingerprints. Why? ‘I’m convinced that there’s a specific oenology for each variety,’ he says. ‘The most appropriate vinification for Chardonnay isn’t the same as the methods that will produce the best Fiano or Greco.’ Moio’s work is further evidence of the radical way in which winemakers are now looking at these singular varieties. Vineyards are being replanted at higher densities, new clones and rootstocks are being used, trellising techniques are being adapted to suit conditions and variety.

One of the first Italian wines I ever encountered was from Campania. It was Lacryma Christi, ‘the tears of Christ’, the most commonly-seen name in the region. Never was a name so appropriate. ‘Jesus wept!’ was my immediate reaction as this semi-oxidised, sweetened white trickled down my throat. Thankfully things have changed. Strangely, in a country that has a dearth of high-quality, flavoursome white grapes Campania can boast of three: Greco, Fiano and Falanghina. The most commonly seen white, Greco di Tufo, comes from vineyards that curve round the hollows and bowls of the high central Irpinian Hills. The combination of poor soil, a long ripening season and cool conditions gives a crisp wine that has retained a remarkable array of aromas; Feudi’s Greco di Tufo smells like scented meadows, the more rounded Mastroberardino Novaserra has a mix of cream and fresh pears at its core. This combination of fragrance and Greco’s bitter almond finish is seen to its greatest strength in Mustilli’s Greco di Sant’ Agata dei Goti.

If Greco has potential, Fiano already oozes class. A low-yielding, late ripening variety, it is made in a number of styles; clean and dry, barrel fermented, late-harvested and passito (from dried grapes). Once again, the region’s grassy fragrance comes across – Mastroberardino’s even has a hint of lavender – but while Greco refreshes with its crisp attack, at Fiano’s heart there’s a subtle melange of honeycomb, apricot tarte tatin, hazelnut, lime blossom and, again, a bitter twist on the finish. Neither variety makes easy wines, but life’s too short to drink endless bottles of boring Chardonnay. ‘If we are going to put a lot of effort into Fiano we first need to understand what Fiano is,’ says Ercolino. ‘We won’t try and ask Fiano for things it can never give us. We’ve got grapes that can give something different.’ Feudi’s top white, the barrel fermented Campanaro, is evidence of the heights that this variety can achieve and now the firm has scaled down the percentage of new oak, Campanaro can rightly be called one of Italy’s best white wines.

The last quality white variety, the enigmatic Falanghina, is a more discreet and delicate entity and is seen at its best in Villa Matilde’s Falerno, with its fascinating mix of ripe pears, fresh flowers and apple blossom. The good news is that even Lacryma Christi – at least in the hands of Mastroberardino – has been reborn as a modern, clean, easy-drinking wine.

If there’s a battle over which white variety is the best, there’s no contest among the reds: here Aglianico rules. Another present from the Greeks, Aglianico (the name is a bastardisation of Ellenico) is a beneficiary of the long, cool ripening season in the central and northern hills. At its best in the volcanic soils of the Calore Valley around the town of Taurasi and near Mondragone north of Naples, it is still a grape that needs to be handled carefully. It can be acidic, tannic and coarse, but when it’s nurtured carefully in the vineyard and winery it’s a grape capable of magnificent heights. PLD’s Taurasi is a classic example, a perfumed mix of gamey notes, strawberry and damson with fine tannins. Mastroberardino’s single vineyard Radice has an aroma of cherry Tunes but a blackstrap heart. Once again though, Feudi dominates, with the gorgeous lifted mix of brambles, tar, and plum in its standard Taurasi, the soft alluring single vineyard Piano di Montevergine, and at the top of the tree, the extraordinary, intense, complex Serpico, where Aglianico has been given a perfumed lift by Sangiovese and Piedirosso.

This combination of the perfumed red fruit aromas of Piedirosso and the dense blackberry/plum of Aglianico is the secret of Villa Matilde’s Falerno del Massico – a serious, rich powerful proposition. Piedirosso on its own, particularly from Mustilli, has a marked similarity to Grenache – all wild fruits, pepper and zingy drinkability.

That there are so many wines to recommend is evidence enough of the changes that have taken place in Campania. That said, even a pioneer like Vincenzo Ercolino is reluctant to hype up what’s happening. For him it’s ludicrous to talk of a revival or a revolution. For him the new Campania has yet to be born. Delivery day, however, can’t be far away.