As the modernisation of Navarra’s wine industry continues apace, so the battle for quality, identity and supply remains won and lost in the vineyards. Modern, hi-tech wineries abound and new investment seems readily available, but control of the raw material provides the key to the future. Independent producers with their own grape supply have a clear advantage and are accelerating away from the field but, with a total of 13,097 hectares (ha) under production and 7,000 registered grape growers in the region the cooperatives are a factor not to be ignored.

Viticultural scene

Navarra’s viticultural scene has drastically changed since the mid-1980s when Garnacha represented about 90% of the vineyard. Today, the figure has fallen to 45% and planting of other varieties continues unabated. There are now 3,511ha of Tempranillo under production and in the ‘new variety’ category 1,170ha of Cabernet Sauvignon and 578ha of Merlot. Of the white varietals Viura holds sway followed by a small but rising percentage of Chardonnay. The change in varieties has also meant a new direction in wine style away from rosé (though still important on the domestic front) to red, now 58% of the production, and an eclectic range of both blended and varietal wines.

The successful remodelling of the industry owes much to the work carried out by EVENA, the local government-backed viticultural and oenological research centre based in Olite. One of its major projects has been the assessment of different grape varieties grown in Navarra’s five winemaking zones: (from north to south) Baja Montaña, Valdizarbe, Tierra Estella, Ribera Alta and Ribera Baja. From a clutch of 40-odd varieties the resulting success and promotion of Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot has been the making of Navarra. Site selection has also come under investigation. Conditions of cultivation vary throughout the region. The Atlantic north is cooler than the Mediterranean south, with a higher average rainfall, while altitudes in Navarra’s hilly terrain vary from 250 to 600 metres. Much of the recent planting has been on the hillslopes of Valdizarbe and Tierra Estella where good natural degrees of alcohol are readily obtained but the cooler conditions provide a longer growing season, an even phenolic maturity and greater finesse in the wines.

The importance of grape supply has been recently highlighted by the growing gap between leading producers and more commercial offerings, the rather lightweight 1997 vintage and the shortfall and consequent price hike caused by the frost affected, but more successful, 1998 and 1999 vintages. ‘Control of quality and price is becoming more difficult and for the future the only way forward is to own your own vineyards,’ says Javier Ochoa of Bodegas Ochoa. As the former director of research at EVENA, he has been at the cutting edge of changes in the region, and has been steadily replanting the family holdings since the 1980s. Tempranillo from a low yielding clone, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and a little Graciano to add colour and acidity to some of the blends are the Ochoa staples. In five to six years Javier Ochoa plans to be two-thirds self-sufficient in grapes.

Other old, established companies have also benefited from a far-sighted approach. Bodegas Guelbenzu in the southern Queiles Valley, an area at one time cultivated by the Romans, was founded in 1851 and by the 1870s winning medals for its wines. After a spell within the framework of the local cooperative a decision to return to independent status was taken in the early 1980s. The 36ha vineyard was replanted with Cabernet Sauvignon, Tempranillo and Merlot and the first vintage of the Bordeaux-style Cabernet-dominated Evo released in 1989. Yields are held to about 40–45 hl/ha and the advantage of older vines can be seen from 1995 onwards when the wines gained in weight and definition. A new project is now in hand to create another winery and plant a further 15ha with Tempranillo, Graciano, Syrah, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Petit Verdot. The resulting wines will only be entitled to vinos de mesa status as the area of planting falls outside the DO Navarra delimitation.

Independent producers

The Chivite family has been making wine in Navarra for nigh-on three centuries, but the development of its Señorío de Arinzano estate near the town of Estella has to be the most ambitious project of the modern era. Since 1988, 170ha of rocky garrigas and clayey river plain have been cleared and planted with Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Chardonnay. The resulting wines are labelled Colección 125. The red Reserva has a dominance of Tempranillo, good fruit, fine structure and improves with every vintage, while the barrel-fermented Chardonnay has steadily acquired balance and finesse. Only French Allier oak is used for the ageing of both wines. A stunning new bodega designed by Rafael Moneo, architect for the extention to the Prado museum in Madrid and new cathedral in Los Angeles, is in the final throes of completion. The computer-controlled, gravity-fed concept is the brainchild of Fernando Chivite, the Bordeaux-trained oenologist and winemaker. Across the valley, Castillo de Monjardín is a relative newcomer compared to Chivite but was one of the first to plant new varieties in the 1980s. Created by the Del Villar family, Monjardín now has 160ha under production and is self-sufficient in grapes. The Chardonnay is planted at 600 metres, just below the 10th-century castle that caps the hill of Monjardín, and is harvested at night. Three cuvées are produced, a crisp unoaked version, a fuller barrel fermented style and a Reserva. The malolactic fermentation is blocked in all three preserving a firm acidity. The reds are also of note particularly the Cabernet-led Reserva and Gran Reserva from the Finca Los Carasoles vineyards.

Other independent producers with projects for extensive new plantings include Marco Real and Príncipe de Viana, while newcomers Palacio de Azcona and Otazu, the most northerly red wine estate in Spain, already produce wines exclusively from their own grapes. Of the better wineries only Palacio de la Vega, now owned by Pernod Ricard, is still completely reliant on purchasing grapes on contract. ‘The fruit is good despite the youthful age of the vines and the sometimes heavy yields but we try to have contracts with the better cooperatives and have some control over methods of cultivation,’ says oenologist José-Maria Nieves.

Among the cooperatives, Bodegas y Viñedos Nekeas in Valdizarbe is a rather singular entity. Founded by eight families in 1994 it took legal status as a cooperative in order to obtain European Union and local government funding but is managed with the same esprit as a private enterprise. Much of the 230ha of trellised vineyard was planted around 1990 and varieties include Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Viura and Chardonnay planted on chalky soils at 500–600 metres altitude. Yields are kept low and the grapes analysed for phenolic as well as alcohol potential prior to picking. The winery itself is modern and efficient and includes a park of some 2,600 American and French oak barrels.

Bodegas Orvalaiz is a more classic cooperative structure with 80 members and a total of 400ha. Created in 1993 it is not yet at the same level as Nekeas but has expanded rapidly and is moving along the right lines. Members receive advice from the technical staff at Orvalaiz from the purchase of the vine through to the moment of harvest. Quality control through analysis is undertaken and in 1999 a new payment scheme was introduced based on alcohol and pH levels as well as colour and the sanitary state of the crop. ‘Yields turn around 60hl/ha as there are a lot of naturally productive young vines but in the future we hope to convince the membership to crop less,’ says oenologist Kepa Sagastizabal. A gradual renewal of the oak barrels should also help improve quality.

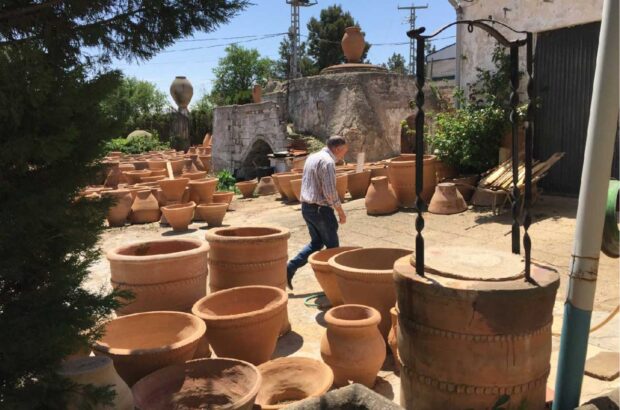

Apart from the new varieties and blends Navarra also provides a discreet production of wines more closely linked to the old regime. As with Shiraz in Australia, a few years back a number of producers realised what a gold-mine they have in the old-vine, gobelet-trained Garnacha, some of which is up to 100 years old. Instead of fruity rosés there is the potential for some heart-warming reds and this seam is being tapped by the likes of Nekeas with El Chaparral, Guelbenzu and Jardin and Marco Real with their full-blooded, almost Aussie, Garnacha.

One of Navarra’s oldest classic grape varieties is Moscatel a Grano Menudo or Muscat à Petits Grains. Virtually at the point of extinction, it is being gradually reintroduced and a modern, grapey, fruit-driven style of wine produced. Harking back to another era, though, Bodegas Camilo Castilla in Ribera Baja still produces a fantastically complex, dark, raisined, oxidised style with Capricho de Goya. The wine is aged for seven years in a mix of large old oak barrels and glass demijohns left out in the sun. Significantly, the vines are owned by Camilo Castillo and have an average age of 75 years. The raw material is still what counts.