- In practice, no serious producer uses white grapes for Chianti Classico anymore.

- The majority of the producers are currently sticking with their Super-IGTs as their most prestigious wine.

- The Chianti Classico Consorzio has been working with producers on improving the clones of Sangiovese.

- Another striking feature of the region is the popularity of agrotourism.

For the past 30 years Chianti has been climbing up the quality ladder with new Chianti blends. During a recent visit to Chianti Classico, I was highly impressed by the depth of quality of the wines that I tasted. Over three days I visited 10 properties and I did not encounter one poor wine. The sole disappointment was a wine tasted and rejected by my hosts in a restaurant.

The 70,000 hectare (ha) Chianti region stretches down from Florence to Siena. The central zone of about 7,000 ha of vines are graded as Chianti Classico.

The Chianti rules

The rules governing Chianti Classico were – belatedly – changed in 1996. Previously the region had been governed by the rules set down for Chianti passed in 1984. Now it is no longer obligatory to include white grapes, Malvasia and Trebbiano, in the blend, although up to six percent can be added if wished. In practice, no serious producer uses white grapes for Chianti anymore. Now, Sangiovese must make up at least 75% of the blend and a pure Sangiovese wine is also permitted. Canaiolo, a local variety, can make up 10% while a number of other red varieties including Colorino, another local variety, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot can make up a maximum of 15%.

The obligatory use of white grapes in Chianti was one of the main reasons why so many estates launched Super-Tuscans, initially as vino da tavola and later under the indicazione geografica tipica (IGT) designation. Now that Chianti Classico rules are more in tune with reality, one might expect producers to phase out their IGTs. However, the majority of the producers are currently sticking with their Super-IGTs as their most prestigious wine rather than renaming it Chianti Classico riserva.

There are a number of reasons for this. The change in the law is recent and many producers will wait and see what happens. Many estates have built up their IGT brand names and are reluctant to change them, especially as consumers have become accustomed to paying more for a Super-IGT than a Chianti Classico riserva. The Cennatoio estate, for example, has developed a range of Super-IGTs, each with their own labels and is unlikely to change this approach just because the legislation has changed. The ageing rules for IGT are more flexible than those for Chianti, especially for the riserva. The 1997 riservas cannot go on sale until this April, whereas a Super-IGT can be released much earlier. Also, once a vineyard has been designated by the producer for production of IGT it is a lengthy process to have it redesignated as Chianti. The prohibition of plastic corks for Chianti Classico may become another factor. Francesco Daddi at Castello la Leccia has been able to reduce the sulphur levels in his IGT wine since he started using plastic closures.

Yield of Chianti Classico

The frequently asked question about yields – how many hectolitres per hectare (hl/ha) – makes little sense unless you know how many vines have been planted per hectare. Traditionally in Tuscany, as in other parts of Italy, planting density has been low – often about 2,000 to 2,500 plants per hectare. Thus, even if the yield was comparatively low, this did not necessarily mean that the grape juice was concentrated. Now, all over Chianti Classico, vineyards are being replanted, and new ones are being created on well-exposed sites. The planting density is being increased to between 4,500 to 6,000 vines per hectare. Still not a high density compared to some vineyards in Burgundy, but then the Tuscan summer drought is far more prevalent than it is around Beaune.

The 1996 legislation limits production to 52.5hl/ha and no more than three kilos per vine. This is considerably less than the permitted levels in some of the classic French regions.

‘The new high density plantings and the new clones will give us the second step up in quality,’ says John Matta of Castello Vicchiomaggio. ‘We will see this come through in 10 years time as the new plantings start to mature.’ The first big quality step started gradually some 25 years ago when producers started bottling their own wine and began to reduce yields, making a more serious offering than the simple light wine that came in straw-wrapped bottles.

As well as the improvements the new plantings will bring, the Chianti Classico Consorzio has been working with producers on improving the clones of Sangiovese under its Chianti Classico 2000 project, which began in 1988. The research prog-ramme aims to identify and develop high-quality clones of Sangiovese, match them to soil types and look at the best planting densities and training systems.

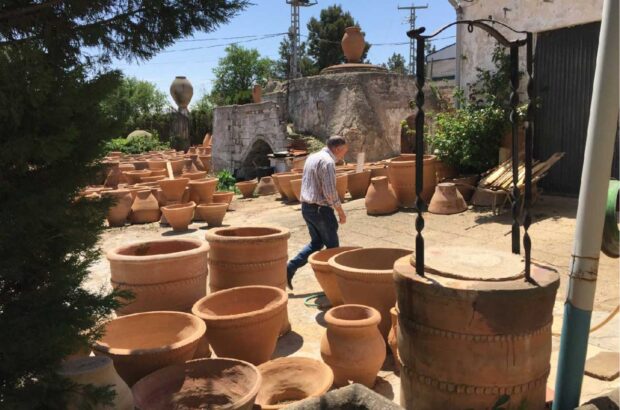

Agrotourism

Another striking feature of the region is the popularity of agrotourism. Many of the estates have self-catering apartments for rent. As well as enjoying the beautiful countryside and the peace, this is a good way of learning and understanding more about what is involved in growing grapes and making wine, throughout the long tourist season which runs from April through to the end of October.

With two excellent vintages in the last three years, 1997 and 1999, along with a good 1998, Chianti Classico’s reputation should continue to climb.

Vineyards

Tenuta di Bibbiano

- via Bibbiano 76, 53011 Castellina in Chianti. Tel: +39 0577 743065; Fax: +39 0577 743202

This is an estate with 27ha, of which 13ha are used for their Chianti Classico. A five hectare south facing vineyard, Capannino, provides the Riserva. There is no Super-IGT as the estate concentrates on making Chianti. Montornello, the straight Chianti Classico, is soft and easy drinking and is principally Sangiovese with a little Canaiolo and Colorino.The elegant riserva is largely Sangiovese with some Canaiolo field-blended in.

Carobbio

- via San Martino a Cecione 26, 50020 Panzano in Chianti. Tel +39 031 971205; Fax: +39 031 890488

Owned by Carlo Novarese, a silk maker in Como, this is a beautiful and isolated 10ha estate. Most is Chianti Classico but there are two IGTs (Leone: 100% Sangiovese and Pietraforte: 100% Cabernet Sauvignon). ‘Having established the brand, we will continue to produce Leone even though technically it could be a Chianti Classico,’ says oenologist, Gabriella Tani.

Collelungo

- 53011 Castellina in Chianti. Tel/fax: +39 0577 740489. Email: info@collelungo.com; website: www.collelungo.com

An 11.5ha estate of Sangiovese is owned by Mira and Tony Rocca, who moved out from Britain to buy the property in 1989. The Roccas initially developed the self-catering side of the estate. However, they became increasingly fascinated by wine and decided to start making their own: 1997 was their first vintage. They make Chianti Classico, a riserva and Roverto, an IGT from 100% Sangiovese.

Castello la Leccia

- Loc la Leccia, 53011 Castellina in Chianti. Tel: +39 0577 743076; Fax: +39 0577 743148

Francesco Daddi runs this 18ha estate, 12ha of Chianti Classico, on organic lines. There are also the six hectares of Casina di Cornia with three hectares classified as Chianti Classico. Daddi wants to concentrate on Chianti Classico, although he has a pure Cabernet Sauvignon IGT. ‘I doubt whether Super-IGTs will last if Chianti Classico gets a high reputation,’ he says. Daddi has planted some Viognier, ‘much more interesting than Chardonnay’. The wines possess impressive levels of concentration due to the low yields.

Castello di Meleto

- 53013 Gaiole in Chianti. Tel: +39 0577-749217; Fax: +39 0577-749762. Email: viticolatoscana@chiantinet.it

Castello di Meleto is an imposing turreted castle that dominates the surrounding countryside from its hill top. This is a large estate with 200ha of vines, chiefly planted with Sangiovese but with about five percent of Merlot, a little Cabernet Sauvignon and, recently one hectare of Syrah. It has an ambitious replanting programme. All three Chiantis (Chianti Classico, riserva and single vineyard Pieve di Spaltenna) are made from 100% Sangiovese. IGT Fiore has five percent Merlot. Apartments are available for rent.

Castello di Monastero

- 53019 Castelnuovo Berardenga. Tel/fax: +39 0577 355789. Email: velm@velm.com

Lionello Marchesi is a manufacturer of seat belts and sun roofs, with factories in Milan and the Czech republic. He previously owned three vineyard properties in Tuscany, one in Chianti Classico, one in Montepulciano and the third in Brunello. In 1993 he was made an offer he could not refuse, yet he could not stay away. ‘Tuscany is like a drug and in 1994 I found Monastero,’ he explains. Built in about 1000 AD, Monastero was an abandoned monastery and village. Reconstruction started on April 11th 1994 and, incredibly, finished on May 14th 1996. Working day and night, 150 people had constructed a tourist and conference centre with accommodation for 350 people.

Marchesi now has 12ha of vines in Chianti Classico and another 75ha in Montepulciano. It is too early to judge the wines from this new venture, but the 1999s in tank and barrel look promising. An estate to watch.

Cennatoio

- 50020 Panzano in Chianti. Tel: +39 055 852134; Fax: +39 055 8963488/. email: info@cennatoio.it; website: www.cennatoio.it

This is a 10ha estate (eight designated Chianti Classico), owned and run by Gabriella and Leandro Alessi, who used to work in the leather industry. This is a high site, with the vineyards planted at 500 metres above sea level. They make a fascinating range of wines including Chianti Classico and a riserva but the prestige end of the range includes four red IGTs. Many of the wines have a sensuous concentration. I found the Chianti Classico riserva 1996 from 100% Sangiovese and Etrusco IGT 1996, also 100% Sangiovese the most interesting. They also make two dry Vin Santos – one white and one red.

Fattoria di Petroio

- Via di Mocenni 7, 53010 Quercegrossa. Tel: +39 0577 328045; Fax: +39 0577 328153

A 13ha organic, determinedly Chianti Classico concentrated estate, with 95% Sangiovese, some Canaiolo and minimal Merlot. ‘Why should you spend $50 for a wine that you don’t know what it is or where it comes from because it has no regional characteristics?’ says owner, Pamela Lenzi.

Castello Vicchiomaggio

- Via Vicchiomaggio 4, 50022 Greve in Chianti. Tel: +39 055-854079; Fax: +39 055-835911. Email: vicchiomaggio@vicchiomaggio.it; website: www.vicchiomaggio.it

Castello Vicchiomaggio has been owned by John Matta’s family since 1963. The vineyards were all replanted then at 2,500 vines per ha but are being replanted again to a density of 5,000 per ha. There are three Chiantis: San Jacopo, and La Prima (90% Sangiovese, five percent Canaiolo and five percent Colorino) and the Riserva Petri has five percent Cabernet Sauvignon. There are also two IGTs: Ripa delle Mandorle (80% Sangiovese, 20% Cabernet Sauvignon) and Ripa delle More which is 100% Sangiovese aged for 18 months in barriques. There’s holiday apartments and a fine restaurant on site.

Villa Sant’Andrea

- San Casciano VP, Tel: (39) 055-8244254

This large estate of 700ha, which includes 50ha of Chianti Classico and 72 ha of olives, has recently installed a new young and ambitious management team. Previously the wines were old fashioned and rather rustic. An estate to watch.