- New wineries seem to emerge by the month, as former waiters, retailers, teachers, life insurance salesmen and jazz musicians heed the mellifluous call of the vine.

- Washington, more than any other region outside Bordeaux and possibly California, is famous for the quality of its ‘Cabernet without the pain’.

- Appellations they may not have, but several locations are recognised as important vineyard areas in their own right.

- Walla Walla, a pretty farming and college town in the corner of eastern Washington, typifies the energy and dynamism of the state.

Crossing Washington State in a small plane is a wonderful experience. If you’re trying to get your head and taste buds around the local wines, it’s also a revelatory one. You set off from Walla Walla airport in Factor 20 sunshine, traversing the Columbia River and the vineyards of the Yakima and Columbia valleys en route to Seattle. From up here, you can see precisely why water rights arouse such controversy in these burnished, desert-like expanses; without irrigation, it is almost impossible to grow vines, although a few courageous souls try in Walla Walla.

For most of the journey, you’ve got a clear view to the horizon. It’s only as you approach the Cascade Mountains that you begin to notice the changes in vegetation and climate, as pines give way to Douglas firs, clear skies to banks of doughy cloud. The differences between the two sides of the Cascades are striking when seen from the air. Imagine flying from Andalusia to England in a few minutes and you have some idea of the contrast.

The dampness and unpredictability of the weather on the Seattle side of the mountains explain why nearly all of the Evergreen State’s grapes are grown in three eastern appellations – Columbia Valley, Yakima Valley and Walla Walla Valley. If you feel like playing Hercule Poirot, you can find vines and even a 14 hectare (ha) appellation called Puget Sound around Seattle itself, but the presence of the distinctly third division Müller-Thurgau, Madeleine Angevine and Siegerrebe is a good indication of the shortcomings of the prevailing climate. Insufficient sunshine and high humidity are the main problems for Seattle grape growers.

Vines are one thing, wineries something else. Two of the state’s biggest producers, Château Ste-Michelle and Columbia Winery, have their headquarters near Seattle, as do several top quality boutique operations, including Matthews Cellars, Andrew Will, Quilceda Creek, McCrea Cellars and DeLille Cellars. They do so for economic, rather than viticultural reasons; all of them buy or grow their grapes east of the Cascades but sell a lot of wine in and around Seattle. For the smaller producers, it’s partly a lifestyle choice, too. Chris Camarda of Andrew Will trucks grapes all the way to his idyllic home on Seattle’s painterly Vashon Island, where he can work – and they can ferment – to the sound of his CD collection. Like everything else which comes to the island, Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon have to take the ferry.

The small winery boom has made Washington a fascinating place to visit at the moment. New wineries seem to emerge by the month, as former waiters, retailers, teachers, life insurance salesmen and jazz musicians heed the mellifluous call of the vine. Half of Washington’s 102 wineries produce fewer than 5,000 cases of wine annually. As well as the Seattle-based operations, there are some great new producers out east in Walla Walla, the other home of boutique wineries.

Spurred on by the new boutique wineries and the example of star producers such as Leonetti, L’Ecole 41 and Woodward Canyon, larger producers like Hedges, Hogue, Columbia Winery, Columbia Crest and Château Ste-Michelle are making much better wines than they were the last time I visited the Pacific North-West in 1991. In a week travelling through the state, I tasted very few poor bottles – not something you could say about California. The vineyards of America’s second largest wine-producing state have changed dramatically in recent years, reflecting Washington’s steady emergence as a source of serious red wines. Thanks to frenetic planting of certain varieties and the slower decline of others, Washington’s 6,700ha of vineyards are now divided almost equally between red and white grapes. It wasn’t always so. ‘When we came to the Yakima Valley in the 1970s, Washington was a white wine state,’ says Scott Williams of Kiona Vineyards. ‘People thought we were nuts to plant red grapes.’

Well, people were wrong. Fashion has snubbed Riesling, Chenin Blanc and Gewürztraminer (the aromatic white varieties which were initially considered Washington’s strongest suit) and embraced Chardonnay, Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon instead. The last 10 years have also seen the introduction of Syrah, Cabernet Franc and smaller quantities of Lemberger, Washington’s name for Central Europe’s Blaufränkisch.

Most varieties grow happily on the eastern side of the Cascades, with the possible exception of Pinot Noir, which performs far better in Oregon. This apart, Washington is a great place to grow Syrah, the red Bordeaux varieties, Chardonnay, Sémillon and, in certain spots, to make sweet wines. It’s also pretty good for Riesling. Despite its drop in popularity (and price), Riesling is still the fourth most planted grape in Washington and comparatively popular with winemakers, if not necessarily grape growers. Last vintage, Riesling was sold at $550 (£340) a ton, while Chardonnay fetched around $1,200 (£750).

Mind you, growing any variety can be tricky in the Columbia Valley. The winters are very cold and can do enormous, and sometimes terminal, damage to vines. The life expectancy of a Washington vine is around 20 years, according to Mike Means of Columbia Crest, much the same as the sacrificial victims the Aztecs used to offer to their gods. Then there’s the problem of access to water. To take only one sub-appellation, the last person to be given precious water rights on Red Mountain was Tom Hedges in 1990. As growers wait to plant more than 200ha of vines, environmental groups argue about dams and the disappearance of salmon from the Columbia River.

On the plus side, points out Mike Januik of Château Ste-Michelle, most of Washington’s vineyards are ungrafted, grown on free-draining sandy soils and phylloxera-free. They also benefit from cool nights, which lengthen the growing season and provide natural balance, and abundant sunshine. ‘We don’t have too many problems with diseases in the vineyards,’ he Adds. ‘Our canopies are pretty open and there’s often a breeze blowing east of the Cascades.’

One virus which has affected Washington is Merlot-itis. Washington, more than any other region outside Bordeaux and possibly California, is famous for the quality of its ‘Cabernet without the pain’. At a recent two-day Vinifera Conference in Seattle, Merlot was the ‘hot topic’, as they like to say on the West Coast – debated, discussed and dissected for an entire afternoon. The questions were many and varied: What to do with it? How to drink it? Where to grow it? How to pronounce it? The one thing no one could argue about was the remarkable popularity of what can be a rather simple grape. Back in 1984, there were only 250ha of Merlot in Washington. Fast forward to 1997, and the grape is everywhere, covering nearly a quarter of the state’s vineyards.

But can Merlot stand alone? David Lake MW, who has been making Merlot from the Milestone Vineyard at Columbia Winery since 1987, says: ‘In many ways, Merlot is Washington’s grape, But I nearly always want to add Cabernet Sauvignon or Cabernet Franc to make it more interesting. People have started to realise that Washington Cabernet Sauvignon is pretty damn good.’ Several winemakers told me that Merlot is surprisingly site-specific. ‘Chardonnay is grown in virtually every region in Washington State,’ says Scott Williams of Kiona: ‘But Merlot really likes certain soils, especially the hezel soils we have in parts of the Yakima Valley.’

It’s not as simple as you’d think to find totally unblended Merlots in Washington. The best ones I tasted during my stay were made by Kiona, Columbia Winery (Milestone Vineyard), Château Ste-Michelle (Indian Wells Vineyard, Canoe Ridge Estate and Horse Heaven), Hogue (the Reserve bottling), Woodward Canyon, L’Ecole 41 and Leonetti, but few of them were as exciting as the leading Bordeaux-style blends. Outside the Right Bank of Bordeaux, very few Merlots can compete with wines like Andrew Will’s 1996 Sorella, DeLille Cellar’s 1995 Chaleur Estate or Woodward Canyon’s 1995 Artist Series.

Washington is much more than a Merlot factory. Thanks to its reliable climate, its vineyards are capable of producing everything from Chenin Blanc Ice Wines to Lemberger and basso profundo Syrahs, via Chardonnay, Sémillon, Viognier, Sauvignon Blanc, Gewürztraminer, Riesling and some very good Bordeaux-style reds. There are also smaller plantings of Nebbiolo, Sangiovese, Zinfandel, Grenache, Aligoté and assorted Muscats as well as the stuff around Puget Sound.

Virtually every winemaker you talk to has different opinions about what Washington does best, although no one bangs a drum for Madeleine Angevine. This is hardly surprising, given Washington’s comparatively recent development as a wine producer of consequence. The first commercial plantings of vinifera grapes were not made until the early 1960s in the Yakima Valley. The viticultural map of Washington is still changing and mutating today, and there are potential sites all over the state which, irrigation permitting, could be developed in the next decade.

This could promote new or even existing varieties above Merlot. It might be the darling grape at the moment, but who’s to say Syrah won’t outshine it in the future? The handful of Syrahs made by Columbia Winery, McCrea Cellars and Glen Fiona are certainly impressive. Just as importantly, Tuscany’s Piero Antinori, who is involved in a joint venture with Château Ste-Michelle, is about to release a blend which includes Cabernet, Merlot and Syrah, rather than Sangiovese. Who knows? Planted in the right place, even Pinot Noir might succeed.

It is tempting to regard the area east of the Cascades as one great, sprawling whole. ‘When they created the Columbia Valley appellation,’ says David Forsyth of Hogue Cellars: ‘They included everywhere you’d want to grow grapes and some places you definitely wouldn’t.’ There are significant differences between areas and sub-areas. Walla Walla, for instance, has twice as much rainfall as the Yakima and Columbia valleys. The problem is that, discounting Puget Sound, Washington has only one large, all-encompassing appellation and two sub-appellations (Walla Walla and Yakima Valley). Confusingly, both the Columbia Valley and Walla Walla include vineyards in Oregon.

Forsyth says that the reality is over-simplified by the existing appellation structure. Pulling inky samples from a series of barrels, he points to marked variation in the flavours and ripening dates of Cabernet Sauvignons from five different vineyard areas: cool, green pepper characters from Sunnyside, an exotic spicy note from Canoe Ridge, refined blackcurrant fruit from Walla Walla, tannin and concentration from the Wahluke Slope, complexity and mouthfeel from Tri-Cities. ‘They all add something to a final blend,’ he says.

Appellations they may not have, but several locations are recognised as important vineyard areas in their own right: Red Mountain, Wahluke Slope and Cold Creek (the plateau along the north side of the Columbia River between Vantage and Othello) and Canoe Ridge (on a plateau above the Columbia River looking across to the wheat fields of Oregon).

Canoe Ridge is the place everyone wants to plant Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot at the moment. As well as the vineyards established by Château Ste-Michelle and California’s Chalone Wine Group (the former a vineyard designate, the latter a winery, both called Canoe Ridge), Hogue and the Columbia Winery have just planted vines in the area and a sub-appellation may not be too far away. Access to water partly explains the popularity of Canoe Ridge, as do less severe temperatures in really cold winters. ‘Water is cheap and plentiful here,’ says Mike Means (who works for both Château Ste-Michelle and its sister winery, Columbia Crest): ‘Pumping it out of the river isn’t. The electricity is expensive.’ Water-wise, growers on Red Mountain are a good deal less fortunate.

Whatever the secret, recent vintages of Château Ste-Michelle’s Canoe Ridge Merlot and Chardonnay, Canoe Ridge Vineyard’s Chardonnay and Woodward Canyon’s Cabernet-based Artist Series reds are very promising for such young vineyards. Add the quality of the wines emerging from more established vineyards on Red Mountain, the Wahluke Slope and especially Walla Walla and you have one of the most exciting vineyard regions in the world.

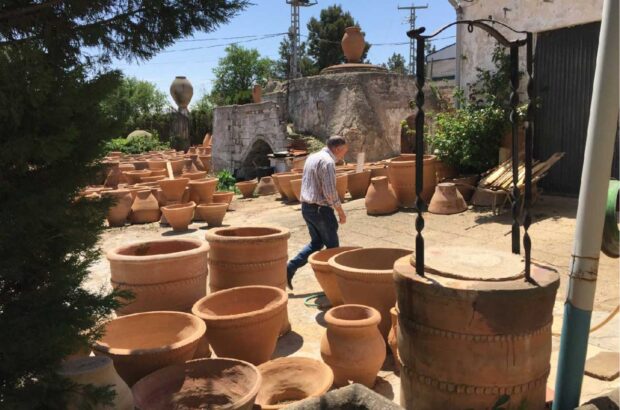

Walla Walla, a pretty farming and college town in the corner of eastern Washington, typifies the energy and dynamism of the state. The pioneers of the late 1970s and early 1980s (Leonetti, Woodward Canyon, L’Ecole 41 and Waterbrook) have inspired a group of new winemakers to set up their own wineries and vineyards. ‘There are new plantings almost every day,’ says Eric Dunham of Dunham Cellars, ‘and more wineries opening every year’.

Walla Walla Vintners, a partnership between three friends with day jobs in psychology, coffee and insurance, is one of the most recent. ‘We’ve been making wine for fun for more than 20 years,’ says Miles Anderson, ‘but until recently we just gave it away to our friends. In 1995 we decided to make some commercial wines. They had to be red and they had to come from this area, because that’s the fruit we know and love.’

The results so far have been outstanding. In only a handful of vintages, Walla Walla Vintners has joined the town’s elite. And the style? ‘I’m the oldest winemaker in the valley,’ Anderson smiles: ‘So I make silky smooth wines that are very much French influenced. If I made inaccessible wines, I might not be here to drink them in 20 years. And what’s the point of making wine if you can’t enjoy it yourself?’