- Priorato’s combination of tiny yields, slate soil and altitude gives wines of astounding concentration.

- Alella is one of the smallest DOs and has always been a hit with closeby Barcelona’s bourgeoisie.

- Somontano , situated on the high plateau between the foothills of the Pyrenees and the Ebro Valley, has an optimistic attitude and has taken a radical approach to rebuilding its wine industry.

- Galicia, until recently a land of rain, forest, sea lochs and bagpipes, has become the trendiest white wine region in Spain.

How often have you heard the following from friends who have just been on holiday to Spain: ‘It’s amazing! We travelled a few miles inland and found a different country just a few miles from the beach?’ It’s true. Close to the ‘British Pub’ and egg and chips there are whitewashed villages, tapas bars, olive groves and the remnants of Moorish civilisation. The Spanish wine scene is similar. We’ve been basking on the Costa Rioja for years, Navarra is a familiar destination, while Ribera del Duero is the chic place to visit. But it’s worthwhile exploring further and discovering the next wave of Spanish regions that’s hiding behind mountains; surrounded by posh suburbia, secreted up river gorges.

Priorato

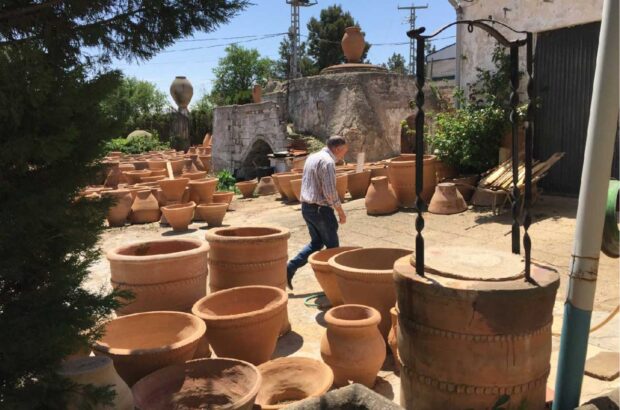

To get to the bleak beauty of Priorato you have to negotiate the tight bends of the road that cuts through the mountain range which fences the region off from the coast. A glance confirms your impression that winemakers must be either masochists or mad to contemplate growing grapes here. But the combination of tiny yields, slate soil and altitude gives wines of astounding concentration. Like all these so-called ‘new’ regions, this is an old area that was on its uppers up until a decade ago. Demand was limited and it made little sense for growers to try and eke out a living from Garnacha vines that yielded a paltry few kilos of grapes. Growers either gave up, or planted Cariñena (Carignan) and happily drank the mediocre results. Thankfully, in 1986, a group of like-minded winemakers joined forces as Costers del Siurana, decided to share facilities and started to revive Priorato. The organisation eventually split, but the pioneers – firms such as Mas Martinet, Alvaro Palacios, Clos Mogador and Carles Pastrana, are still there. What the new guys began, as well as a belief in the region’s potential, was better winemaking practices to control the huge levels of alcohol, tannin and occasional volatility that spoiled many of the old-style wines; the introduction of other varieties, like Syrah and Cabernet; and better wood handling. The resulting wines fetch high prices and are as uncompromising as their environment, but the best are among Spain’s finest. These days you can choose from the highly extracted Masía Barril, whose wildness may not be technically perfect, but represents the best of the old school; or, from the new wave, the heady 1992 Clos l’Obac, the overwhelming dark power of Alvaro Palacios and even an elegant 1989 Clos Mogador from the first Costers del Siurana vintage. Priorato remains an undiscovered gem.

Alella – the sound of the suburbs

I had my doubts Alella existed when I tried to find Marqués de Alella’s immaculate modern winery, getting hopelessly lost in the process. It was no great surprise. At 400 hectares, Alella is one of the smallest DOs and is in danger of shrinking further. The problem isn’t poor wine, but the fact that Barcelona is only 20km away and Alella has always been a hit with that city’s bourgeoisie. First of all they drank the wine, then they decided to build homes in the picturesque hills and valleys that run parallel to the Mediterranean. Now, if you were a grower with two hectares of vines and an estate agent came along and offered you the moon for your land to build houses on, what would you do? A lot have taken the money, leaving a tiny amount of vineyard and only Marqués de Alella as a producer of any real worth.

The bodega (and the region’s) main grape variety is Pansa Blanca, a local mutation of Penedès’ Xarel-lo which has developed considerable finesse. The bodega produces an impressive range of wines, from an austere, haughty Cava, to the elegant Clasico (100% Pansa Blanca) and a barrel-fermented Chardonnay. When you taste what one quality-obsessed producer can make from this mix of indigenous and foreign grapes you long for someone else to offer support. The fact that it stands basically on its own doesn’t help Alella’s cause. ‘There’s a future here,’ says Manuel Moreno, who imports Marqués de Alella, ‘but as it stands, only for one firm’.

Somontano – a new mould

On paper Somontano is not much better off, with only two bodegas of any reputation: Viñas del Vero and Enate. The difference here is that there is land available and an optimistic attitude. Situated on the high plateau between the foothills of the Pyrenees and the Ebro Valley, Somontano has taken a radical approach to rebuilding its wine industry. Winemakers like Viñas del Vero’s Pedro Aibar realised that there was little use in persevering with Moristel and Macabeo and so he researched how other European varieties performed. The result, according to Freixenet’s Philip Rowles, who has monitored the development of Viñas del Vero from day one, is that Somontano has become a young winemaker’s paradise. The fact that there was no outstanding indigenous variety gave winemakers like Aibar a blank canvas to work on. He didn’t just look to see what his neighbours were up to, but studied what was being done in similar cool-climate sites in Australia and Italy. ‘Chardonnay wasn’t planted because it was fashionable,’ says Rowles, ‘but because Pedro looked at a site and thought that it grew well there.’ For Rowles, the subsequent success of Viñas del Vero and Enate, vindicates this internationalist approach. ‘The lesson is that if a winemaker wants to make fine wine he can,’ he argues. ‘If there are good local varieties they can be used; if not, work out what will work best on specific sites.’ Viñas del Vero’s elegant, barrel-fermented Chardonnay is well ahead of Enate, though that bodega’s single vineyard 234 is a sound, attractive wine. In reds you can see why Moristel was ditched: the alternatives are much more worthwhile. Take Viñas del Vero’s Pinot Noir – a juicy little number with a touch of blueberry fruit and a whiff of the farmyard. Like many of the best of the new wave of Spanish wines, it seems to have taken the fruity ripeness of the New World while still remaining European. It isn’t top Burgundy, but it’s seriously nice wine. The Enate range follows a similar theme – cool, red-fruit accented wines that make great drinking.

Galicia

Like these other regions, until recently this land of rain, forest, sea lochs and bagpipes was an isolated part of Spain whose wines were rarely seen outside its borders. In recent years the DO of Rías Baixas has become the trendiest white wine region in Spain thanks to an insatiable demand for its best white variety, Albariño, prompting an explosion of new bodegas – though there’s a gut feeling that many of these estates are just fashion accessories for people with money to burn. Though Rioja firms Marqués de Murrieta and La Rioja Alta have showed a way forward with Pazo de Barrantes and Lagar de Cervera, many Rías Baixas wines are simply not worth the high prices being asked. When handled properly in the vineyard and winery, Albariño can give wonderful aromas and great texture – as winemaker Santiago Ruiz proves year after year – but he is an exception. Increasingly, buyers are travelling up-river to regions such as Ribeiro, where warmer conditions give wines with greater weight, like Arsenio Paz’s Vilerma (a blend of Treixadura, Albariño and Godello).

A few miles further upstream, where the Sil joins the Mino, are the terraced cliffs of Ribera Sacra. Though plantings in this DO are dominated by Mencía and Palomino there are pockets of Godello, Albariño, Malvasia and Treixadura on the best sites. The top wines are among the best in Galicia. Once again this is a forgotten paradise that’s teetering on the brink thanks to under-investment and lack of viticultural advice. Taste Moure’s Abadia (from Albariño) and you drool at the thought of more wines like this. But there’s little incentive for the new generation to follow in their fathers’ footsteps into the vineyards.

Further up the gorges of the Sil you arrive in Valdeorras which, according to Laymont & Shaw’s John Hawes, has been the least known DO in Galicia, though this anonymity, he feels was a blessing as the wines weren’t all up to scratch. Despite this he imports Valdesil, a delicious white, made from Godello. More of this and Adnams’ tasty Godeval and things will be looking up.

All these top Galician whites share aromas of white peach, pear, almond and apricot. They seem delicate, but then surprise you with their rich mouthfeel. Galicia remains a mixed bag, but full of potential.

What these regions demonstrate is that there’s more to Spain than Tempranillo and cheap price tags. Importantly, each has its own speciality and is developing in a highly individual manner. This isn’t only good for the consumer, but is healthy for the development of the industry. That said, only Somontano and to a lesser extent Priorato can be said to have made a complete break-from the past. All these regions have been kick-started into life by private investment rather than by breaking through the conservative deadlock of the co-op system, but it’s still small growers who hold the key to success or failure. There’s no surprise that the best producers have control over their vineyards, and only respect tradition if it adds to quality. But until growers are encouraged to produce high quality fruit for premium wines there is little hope for a mass conversion to these new ways. The wine emerging from these areas is evidence this process is starting, but there’s plenty more work to be done.