The facade of Château Pontet-Canet, a Médoc growth classified in 1855, exudes an aura of timelessness. However, although its ancient stones conceal an efficient, modern business, producing a wine of such prestige is a commercial enterprise quite unlike any other because the product is a living organism. Jean-Michel Comme, the château’s technical manager, and owner and manager Alfred Tesseron’s right-hand man, explains that working for a classed growth gives people a sense of history and belonging. ‘We are a small, well-integrated team, almost a family, with a sense of responsibility to the vineyard,’ he says.

Comme is in charge of production and personnel while Tesseron looks after public relations, marketing and, naturally enough, the business and financial issues. He has two team leaders working under him, one in the vineyard and the other in the cellar, but he personally organises each day’s tasks, taking account of the weather and the time of year. Recent French legislation has reduced the working week from 39 to 35 hours, without loss of pay, which places a heavy burden on small businesses. Wages plus social security represent 50–60% of the estate’s running costs. Today the wine business is booming but wine has never been a stable commodity. There has been a run of great vintages but farmers are never immune to imponderables such as frost, hail, disease or vine pests.

A permanent staff of 30 vineyard workers is maintained to cope with seasonal tasks in the 79-hectare vineyards: pruning, trimming, trellising, leaf-stripping and green harvesting in August. In the intervening lulls, vignerons are kept busy on other jobs. However, this apparent overstaffing means that the same person looks after the same vine at each stage of its development. When part of the crop is cut during the green harvest, it is never a haphazard choice, and each of the 600,000 vines on the estate is checked by a vigneron.Vines for the grand vin are 40 years old, which represents nearly two generations. Comme has worked at the château for a mere 12 years, so the vines he is responsible for planting only produce grapes for the second wine, Les Hauts de Pontet. The vines used for the Pontet-Canet label were planted and cared for by his predecessors and Comme, in his turn, has a duty to future generations.

In addition to the 30 vineyard and cellar workers, the château has an administrative and household staff of five. Nathalie, Tesseron’s personal secretary and receptionist, has her office out front. She is always ready with a smile and a welcome for visitors to the château. José, the Portuguese maître d’, has been with Tesseron for nearly 19 years, has the bearing of an old retainer. Butler-cum-housekeeper, José’s duties include running the château, preparing meals for guests and serving at table. The dining room can seat a maximum of 30, but Tesseron prefers more intimate receptions. There are three or four guest rooms which may be made available for friends or privileged visitors and José is there to welcome them in the evening, serve breakfast and make up their rooms. On average, over the year, there are perhaps two receptions a week, but in quiet periods there may be none and at peak times two a day. When there are fewer than 10 guests, the cook prepares the meals with help from a vineyard worker, but if the numbers are higher an outside caterer is called in.

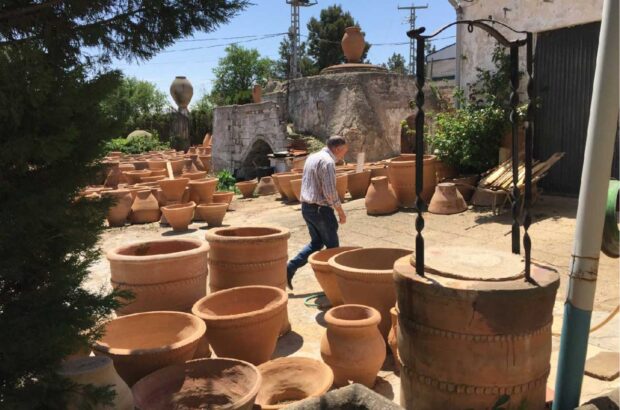

The vendanges is the culmination of a year of intense labour and 120 pickers are needed to harvest the crop. Regular as clockwork, a bus load of 70 farm workers arrives on time each year from Portugal. The remainder come from the local community, usually the same people, glad to earn the extra pocket money. However, to get the 50 hands he needs, Comme knows he must recruit 70 because so many drop out. In addition, there are one or two vagabonds he can count on, like Gerhard, a German, who wanders across Europe camping out in all weathers. For years David, a Scotsman, appeared at harvest time dressed in a kilt… During the vendanges, key positions are taken by château staff. Two teams of three women work eight-hour shifts, from six in the morning to 10 at night, preparing the three daily meals. Bathrooms and toilets are one person’s full-time occupation, together with a maintenance repair man. With 130 people using the conveniences, at least one gets broken every day. Staff also drive the six tractors bringing in the harvest, and there are four more at the reception bay unloading the tubs with forklift trucks. A mechanic is kept busy full-time with on-the-spot repairs. The two sorting tables at the reception bays each have a staff member in charge. There is one person on the payroll, though, who is exempt from involvement in vendanges-related activities: the full-time stonemason. This dedicated craftsman helped restore Narbonne cathedral and his job today is to maintain the facade of the château in all its glory.

Feeding the hungry mob

To keep them going, the meals for the manual workers need to be plentiful and nourishing, and Tesseron insists on quality nutrition, so no ready meals or frozen foods are served.

Fresh produce is bought and prepared in the kitchens, including large quantities of potatoes, which are peeled and chopped for chips. The Portuguese consume large quantities of rice with cod, which they claim to prepare in 150 different ways, and this national taste is taken into account.

This is a wine château and although wine consumption is not limited, it is monitored. Men who drink too much get out of hand, so staff keep an eye on the tipplers. Most châteaux have done away with the end-of-harvest feast, or Gerbe Baude as it is called in the local patois, because of troublemakers. Pontet-Canet has re-instituted this tradition, but with some misgivings and Comme admits that he is always relieved when it’s over.