The Douro’s soils were long seen as one and the same when it came to growing Port grapes, of whatever variety. But thanks to new approaches from the major shippers, the regional subtleties of terroir are now being appreciated. Margaret Rand reports

Quick links:

It was hiding in plain sight, of course; it’s just that nobody was looking. The shippers’ eyes were focused on their fermentation lagares and on their blending rooms in Vila Nova de Gaia. The growers’ eyes were focused on the shippers. Underneath their feet was the terroir that made one Port elegant, another muscular, another aromatic. They were aware of it, but they were looking the other way.

If you went to the Douro 20 years ago and asked about terroir, the usual reply was that Port was about blending. Yes, altitude and exposure matter – look at the Port vineyard classification, which took those factors into account nearly 70 years ago, and ranked warmer, low-altitude vineyards above those at 500 metres, and steep ones above those with a walkable incline. But soil? It’s all schist, they said, and it’s all the same. The Port demarcation simply outlines a vast area of schist soil. End of story.

In fact, that was only the beginning of the story. This is about how the shippers discovered terroir; and they did so by becoming growers. Part of that narrative is to do with table wines. Says Paul Symington of Symington Family Estates: ‘Table wines have made the Port trade see itself in a different way. When we were just shippers, it made no sense to say where the grapes were from, because they weren’t our vineyards. It was a profound change when shippers became growers.’

They didn’t become growers to make table wines but to safeguard their supplies of Port grapes, as sales of Late-Bottled Vintage promised to rocket. Then, because they foresaw labour shortages in the Douro, they also wanted to mechanise. To mechanise their terraced vineyards they had to plant them differently, and to do that they had to understand what was in them.

Those terraced vineyards housed dozens of interplanted grape varieties, some identified, some not. Terroir, if anyone had considered the matter, would have been impossibly entangled with grape mix. Every vineyard had a different field blend: how could you possibly say which differences in the wine were down to vines and which to terroir? First you had to evaluate the grape varieties: only then could you consider the terroir.

The work on grape varieties reduced the ideal Port vineyard to just five, planted in blocks. And it raised the average (though not the top) quality of Port. But Port grapes need exuberant colour, tannin, aroma and flavour. A bit of overripeness doesn’t matter for Port: extraction is short and sharp, and a few raisined grapes won’t show in the final blend. For table wine it’s a different matter.

Schist and granite

As we’ve mentioned before, think of Douro terroir and you think of schist. There’s the odd bit of hard blue schist, especially at Foz Côa in the Douro Superior, but usually it’s more friable yellow schist. Says Cristiano van Zeller of Quinta Vale D Maria: ‘Yellow schist has different textures too: you can feel the difference when you’re walking.’ Granite breaks through in places, but granite not only makes wines that are too light and acidic for great Port, but unless it’s weathered and broken down, is impenetrable to vine roots.’

Schist can be impenetrable too, if the strata are horizontal. But horizontal is not a word that springs much to mind in the Douro: the strata are folded and nearly vertical. The roots can force their way between the layers – and with less than 1.5% organic matter in the soil, the roots have to go well down to survive dry summers and freezing winters. When producers started dipping their toes into table wine, the results were mixed. ‘The wines we used to serve were indescribable’, says Symington now of his early efforts. ‘In 1998 and ’89 we started taking it seriously. About 15 years ago I thought we’d have to plant Cabernet Sauvignon here [for table wines]. I saw raisined fruit, and wondered, how can we make something beautiful?

Today’s table wines have silky tannins and aromas of blackberry, juniper and cistus wrapped around a firm black-fruited core, with alcohol in balance and oak pulled back. To make wines like these, from vineyards intended to give maximum colour and tannin, meant first looking at altitude.

António Magalhães, head of viticulture at The Fladgate Partnership (Taylor’s, Croft, Fonseca), says that the Douro vineyards were originally high up, but moved down to lower, hotter places because that’s what the Port shippers wanted: every 100m of altitude means a 0.5ºC difference in temperature. For table wines they started moving back up. ‘Higher vineyards, at 600m, are now valued because they give freshness,’ says Symington. ‘I’ve just planted

two hectares of [white] Viosinho and Arinto at 500m. It’s the first time I’ve ever planted white grapes in my life.’ Dirk Niepoort gets reds and whites from vineyards as high as 800m: ‘And we’re working more and more with granite soils. We haven’t acidified anything since 2009.’

Site specifics

Everybody loves granite now. Quinta do Vale Meão, in the Douro Superior, has lots of it. Says oenologist Xito Olazabal: ‘You can actually make good wines for Port from granite, especially white. But it’s less concentrated. We decided two years ago to make a single-vineyard Touriga Nacional from 100% granite [Monte Meão]: the wines have too much personality to blend with other wines. Granite gives different tannins and structure, more like Dão,’ whose terroir is mainly granite.

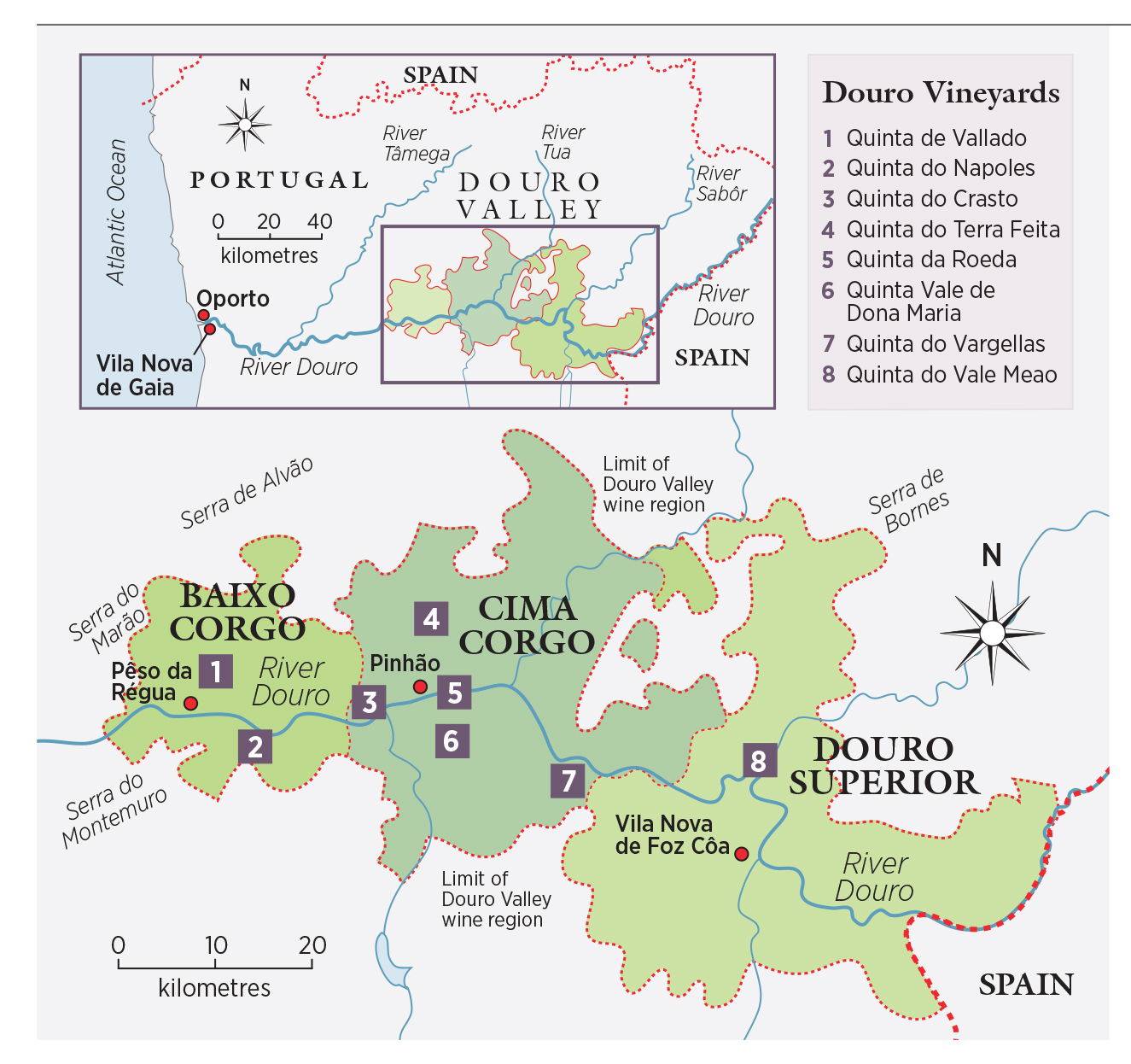

Vale Meão has alluvial sand, schist, granite and gravel all rubbing shoulders: it’s very different to the Cima Corgo, where most top Port comes from. It’s also much hotter and drier. Irrigation is necessary, and it’s proving more useful for table wines than for Port. The Cima Corgo, steeper, contoured with terraces, and itself hotter and drier than the Baixa Corgo, the source of most basic Port, now gives both table wines and Port. Which leads to an obvious question: are we seeing a separation of the Douro into different areas for Port and table wine?

The answer is: up to a point. But it’s complicated. Quite often the sites rated less highly for Port are better for table wines, and altitude can be a big part of this. Exposure is also important, and you can hardly get two consecutive metres of vineyard with the same exposure. For Port, you might wantsouth- or west-facing vines; for table wines, often north-facing, or at least with some afternoon shade.

‘When I started,’ says João Alvares Ribeiro of Quinta do Vallado, ‘we had two neighbouring parcels, with slightly different exposures. One gave one of the best wines of the quinta and the other the worst. They were planted at the same time and the grape mix was probably the same. I thought it might be a problem of extraction or something, but it was always the same. It was just a question of exposure. It makes an enormous difference.’

According to viticulturist Pedro Barbosa of Vale Meão, getting away from the river helps a lot. ‘On the one hand the river increases humidity, but on the other, it’s hotter,’ he says. ‘If you go away from the river, and 500m up, you can find sites that are 3ºC to 5ºC cooler. High, south-facing vineyards away from the river are very interesting for white.’

Quintas that make both table wine and Port – like Vesuvio, which is north-facing, with vineyards at 120m-300m – use the highest vines (ripening 10 to 15 days later) for table wine. Dirk Niepoort’s Quinta do Nápoles, opposite Quinta do Crasto, was bought by Dirk’s father for Port; Dirk didn’t think it would amount to much, but it turns out to be very good for table wine, especially reds. The Alijó and Murça areas of the Cima Corgo are proving popular for whites, says Vallado’s João Alvares Ribeiro: ‘We buy 60% of our fruit from cooler areas.’

But it’s not yet possible to draw lines in the map to say, ‘here is Port, here is table wine’. It can only be done vineyard by vineyard, even parcel by parcel. And the more you look, the more you can see.

Written by Margaret Rand