In partnership with ARAEX Grands

Sherry comes from Southern Spain, in the triangle formed by the towns of Jerez, Sanlúcar de Barrameda and El Puerto de Santa María.In partnership with ARAEX Grands

Complete guide to Sherry

Dry styles

Manzanilla and Fino

Sherry is a white wine that is typically matured by being passed through a series of 600litre butts, in a system known as a solera. There are two main styles. The first is known as ‘biological’. That’s to say they are fortified to a minimum alcohol of 15% and matured under a layer of flor, yeasts which prevent the wine from being exposed to oxygen. The flor consumes the sugars and other components, and gives rise to acetaldehydes, which are such a distinctive characteristic.

Manzanilla (the lightest style, matured in Sanlúcar’s bodegas) and Fino (the bolder style, from Jerez and El Puerto) are both dry wines, both made from the Palomino grape. Manzanilla that has been aged for longer than usual, until the flor weakens, is known as Manzanilla Pasada. It has a deeper colour, and a more complex palate.

Five top Spanish wine regions to visit

En Rama

A recent trend in Fino and Manzanilla is the release of En Rama versions. These are Sherries drawn from the butt when the flor is thickest, typically in the spring. They often have more character and complexity as ‘En Rama’ means straight from the butt. However producers do differ in the degree of filtration they do before bottling.

Pagos

Another trend is terroir. Sherry is famous for its brilliant white Albariza soils of chalk/limestone. There have always been great Pagos or vineyards in the best area (known as Jerez Superior), and with the revival of interest in fine Sherries they have started to be named again, as a new generation of producers become interested in identity.

The Jerez region. Credit: Maggie Nelson/ Decanter

Amontillado, Oloroso and Palo Cortado

The second main style of Sherry is ‘oxidative’, wines that gain a deeper colour and nutty complexity from ageing without. Amontillado is the Sherry that sits on the fence: it starts its life as a Manzanilla or Fino. In time the flor dies away, and the wine develops a nutty complexity, while still retaining the delicacy of its early years. Amontillado will be between 16% and 22% depending on its age and concentration.

Oloroso is selected at the outset, typically with a heavier must, which is then fortified to 17%. This prevents flor developing. As it ages, the water evaporates and it becomes ever more concentrated and complex. Oloroso is between 17% and 22%.

Palo Cortado has become something of a cult – partly because of the finesse of the best examples, and partly because of its mysteriousness. Palo Cortado is described as having the aroma of an Amontillado with the palate of an Oloroso. It certainly depends on the skill of the cellar master in identifying the best butts. It is from 17%-22%.

These categories can be released with an age indication of 12 or 15 years, and an age certification of 20 or 30 years. There is also a category of vintage Sherry.

Five Spanish grape varieties to know

Sweeter styles

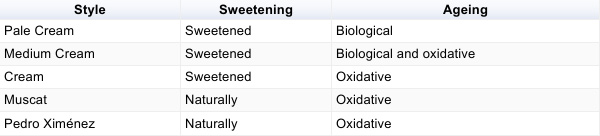

Pale Cream is a Fino/Manzanilla, tailor made for export markets such as the UK, which has been sweetened by rectified concentrated grape must. Medium includes a wide range of sweetness from 5g/l to 115g/l. Cream is a blend of Oloroso and Pedro Ximénez. There are two naturally sweet wine styles. Moscatel is found on sandy soils and produces a deliciously grapey Sherry with a balanced sweetness at about 160g/l; 15%-22%. Pedro Ximénez grapes, when sun-ripened, make one of the sweetest wines in the world. Exceptionally dark, dense, with powerful dried fruit and liquorice notes. More than 212g/l; 15-22%.

The cellar master

The contribution of the cellar master is fundamental in managing the soleras. The position of each butt in relation to the damp albero soil, the humid breezes through the window, and the summer heat, means each butt develops slightly differently. They have been instrumental in identifying exceptional butts, and assisting the new generation of negociant businesses based on cellar selections.