Chateau Latour and Napa Valley Araujo owner Francois Pinault has just been named the eighth richest man in France, but this archived column from Andrew Jefford considers the wide disparity in value that exists in wine and reports on a story seldom reported yet arguably much more typical.

This Jefford on Monday article was originally published on 25 August 2013.

I’ve never, alas, tasted an Araujo Estate Cabernet Sauvignon grown in the Eisele Vineyard, Napa Valley. My newly acquired enthusiasm for great Napa Cabernet, though, suggests that I’d like it a lot.

What was ‘the undisclosed sum’ paid by the Pinault family in late July to bring Araujo into the Latour stable? No one knows quite which two digits preceded the million dollar abbreviation. (Or were there, even, three?) The colossal disparity in land values, though, between Napa Cabernet vineyard and those of Coonawarra, Margaret River, or indeed any other location in the ‘New World’, is remarkable, and merits reflection by landowners in those other key Cabernet regions.

Let me tell you about a very different vineyard transition. You’ll never have heard of the seller or the vineyard, and may not have ever heard of the buyer, either. The sum involved was insignificant. Why am I bothering you with it? More later.

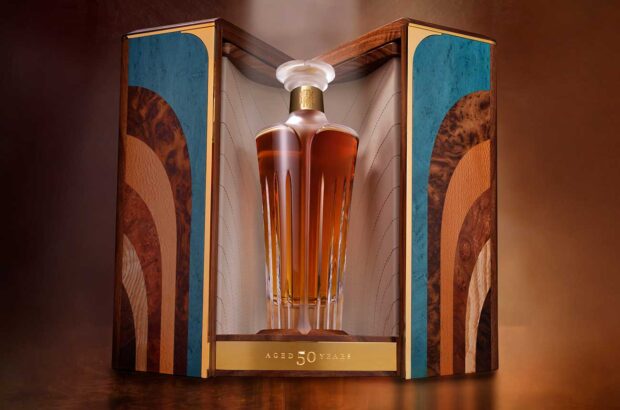

On the afternoon of June 25th, I stood with a Wachau winegrower called Peter Veyder-Malberg. We looked across to a terraced vineyard on a slope a couple of hillsides away called Brandstatt. It’s photographed above.

Veyder-Malberg is an incomer to the Wachau, a former Vienna advertising executive who quit, learned winemaking at Pine Ridge, Villa Maria, Esk Valley and Franz Keller then, after working as general manager for Graf Hardegg in the Wienviertel, bought a few morsels of terraced vineyard for himself.

Why terraces? “My idea was to farm land where tractors have never driven. We’re in the north. It rains. Tractors do a huge amount of damage when driven on wet soil. This work is more like gardening, and that was fascinating to me.” He concentrated his purchases on the Spitzer valley at the Wachau’s western end. “People on the banks of the Danube say that these vineyards never get ripe, but I thought that would be interesting with climate change. And most growers here take their fruit to a co-operative, so I could just afford the land prices.” He’s acquired 20 tiny parcels up and down the Wachau, making about four hectares.

He pointed across to Brandstatt: a steep hill whose terraces were half-abandoned. “I bought that vineyard in 2009 from an old lady in her eighties. She was called Margarete Siebenhandl – a tiny lady, very slender, with a very precise voice. She was unmarried. She’d tended those vineyards all her life. She used to come up here every day. You see that hut?” A little black shack crouched at the bottom of the vineyard. The slope meant it was sited at a crazy angle; it looked as if it would slide away at any moment. “That was where she used to shelter from the storms. She used oak stakes for the vines. She used to remove them every winter, so no one would steal them, and put them back in spring. But one day she couldn’t come up the hill any more. So she asked the firemen to cut all the vines off, and the vineyard fell into ruin. She went to live with her sister. I talked to the sister, who told her ‘This man wants to buy your vineyard’. The old lady didn’t believe it. No one thought that vineyard would ever come back to life. Many growers in this part of the valley are old. Their backs go, and then they have to give up, because the children are all happy with their jobs in Vienna.”

Veyder-Malberg reclaims four terraces of Brandstatt every second year: he hasn’t got the funds or the time for more than that, but he does a thorough job, restoring the walling as well as clearing and replanting. In six years’ time, he should have finished his restoration of this beautifully exposed mica-schist vineyard; he’s planted Riesling (“it’s too free-draining for Grüner”), and he has high hopes for it. What, I asked him, did Margarete think of his work?

“I felt very sorry for her when I heard her story. Later I called back and talked to her sister. I asked if I could show Margarete what I was doing. ‘No,’ she said; ‘she’s in bed and doesn’t get up any more now. But anyway I told her,’ the sister went on. ‘When she heard that her Brandstatt was going to be replanted, she cried.’”

For some reason, I haven’t been able to forget tiny, aged Margarete Siebenhandl, who walked herself up the steep hill ever day of her working life to look after her vines, who lived on the modest sums her grapes brought her at the co-op each year, and who felt, when her strength failed, that she had to ask firemen to destroy her life’s work because no one would now want it. I suspect it’s a far more typical story than the good fortune of Bart and Daphne Araujo — in all the difficult parts of Europe, and in all the have-a-go places in the New World where high hopes later crumble. Every time you drink a European cooperative-produced wine, it will brim, silently enough, with stories like Margarete’s. At least this one had a happy ending.