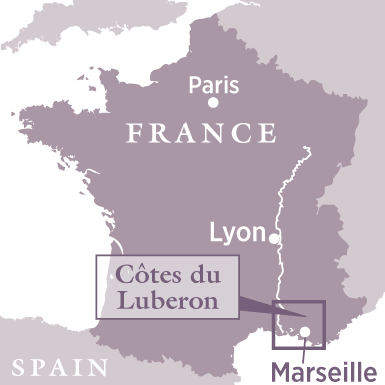

With its pretty hilltop towns to please walkers, and superb food and wine for gourmands, ‘Peter Mayle country’ is still as enticing as ever, says Mary Dowey. Read her Luberon travel guide here.

Luberon fact file:

Planted area 6,000 hectares

Main grapes White Grenache Blanc, Clairette, Vermentino, Bourboulenc, Roussanne, Marsanne, Viognier Rosé Grenache Noir, Syrah, Cinsault Red Syrah, Grenache Noir, Mourvèdre, Carignan

Soil types Varies, but includes sand, limestone scree, red clay

Quick links:

– Six of the best estates to visit

– Where to stay, shop, eat and relax

Introduction:

Has anybody not heard of the Luberon? Some 25 years ago the world would have put its hand up in answer. The pretty countryside tucked under the hem of the Southern Rhône was a sleepy backwater– east of Avignon, north of Aix-en-Provence but as vague in its impact as the mountain of the Grand Luberon blanketed in autumn mist.

That changed in 1989 when A Year in Provence became an immediate bestseller. For readers everywhere from Vauxhall to Vancouver, Peter Mayle’s account of life around Ménerbes gave the Luberon a clear, compelling identity. Here was a place where you could feast your eyes on ravishing landscapes, gorge on truffles, drink decent local wines and move through life at the same slow pace as the ancient Citroëns on the roads. The book transfigured the whole image of Provence, making the hotspots of the Côte d’Azur seem infinitely less appealing than the languid Luberon.

Or so it seemed to the English-speaking world. In fact, the Luberon’s emergence as a tourist destination had begun in the late 1960s. Wealthy Parisians came south in summer to restore quaint, pitifully deserted villages such as Oppède-le-Vieux, while well-to-do Marseille families migrated north, swapping the bustle and heat of the coast for rural calm and a less sweltering climate.

From a wine point of view, those cool summer nights are vital. The long ridge of the Montagne du Luberon, rising to more than 1,000m, cools the region, slowing down grape-ripening. So the warm southern Rhône’s southernmost appellation is more capable than many further north of making crisp whites, delicate rosés and elegant reds in which cool-toned Syrah tempers heat-loving Grenache.

For all seasons

Visitors still see the Luberon as a summer destination. Even in the August heat it is greener than other parts of the south, its melon fields and orchards watered by the Durance river through an ingenious Roman channelling system. Heaped with impeccable produce all year round, the markets in summer seem especially enticing, with cherries, peaches, apricots and Cavaillon’s famous melons on offer alongside delectable goat’s cheeses – the local star among them, Banon, hogging attention with its distinctive chestnut-leaf wrapping.

Summer is the time to enjoy this bounty in the Luberon’s most idyllic setting – on a terrace of sun-warmed stones shaded by a canopy of vines. Because the region’s raw ingredients are so good, talented chefs like Edouard Loubet, Reine Sammut and Eric Sapet count among its most passionate supporters, spinning magic out of everything from poppies and thyme honey to 40 kinds of basil.

But other seasons can be just as entrancing, not least because the sky is almost always blue. Spring brings blossom and tender asparagus; autumn, wild mushrooms and the scent of woodsmoke; winter, diamond-bright light, truffles and the olive harvest, followed by the grassy taste of the new oil.

To compound these seasonal variations, it is often said that the Luberon can show two faces at any time of year. The one with vineyards, olive groves, orchards, lavender fields and red cliffss miles warmly. The other, with its stark grey mountains, forests, gorges and bare limestone dwellings known as bories, appears more austere, especially under the icy blast of the mistral wind.

Even the picturesque, precariously perched villages – Gordes, Ménerbes, Bonnieux and the rest– look wary and guarded, as if they still fear the sort of attack which, in 1545, saw 11 Waldensian (Protestant) communities massacred in one night.

Small growers, big investment

But privacy is granted to outsiders. Celebrity visitors including Ridley Scott, John Malkovich, Tom Stoppard, Demi Moore, Sheila Hancock and Viscount Linley have generally been left in peace. Sophisticated enough to cater to their needs (with antiques shops and a few designer boutiques), the Luberon has managed to retain the rural charm which made it so appealing in the first place. It’s a land of small farmers. Go to Coustellet farmers’market on a Sunday morning and, from the home-grown garlic on one stand and the home-cured olives on another, you’ll see just how small.

The wine scene reflects the same mix, with a high proportion of individual growers, their families here for generations, and a low but significant number of glitzy investors from elsewhere. The Côtes du Luberon appellation, now known as Luberon, was created in 1988. Although it has taken longer to develop a momentum than has the region as a whole, there are 49 wineries today compared with 25 just 15 years ago. (Houses are expensive, but vineyard land remains relatively cheap).

Wine prices are a shade ambitious simply because thirsty visitors with cash to spare will pay them. On the other hand, quality is generally highand, thanks to those same visitors, a fair number of wineries are open to the public. With a major wine tourism initiative at the planning stage, some estates already offer picnics and vineyard walks.

For anybody who can face the occasional hill, walking is the ideal way to get around – especially as the entire Luberon appellation sits within the region’s vast national park. Why not pick up a wine trail booklet at the tourist office and see how much you can manage on foot? And if you tire, a restorative restaurant is never far away – as Peter Mayle discovered all those years ago.

How to get there:

By plane to Marseille or Avignon (flight time less than two hours from various UK airports); then a 30-minute drive to the vineyards

By fast train (TGV) to Avignon from London St Pancras (about six hours), plus a 20-minute drive

More information visit provenceguide.co.uk and vins-luberon.fr

Written by Mary Dowey