The 13th generation has just started working at this famous Alsace producer, notable for setting the rules for (and later boycotting) the region’s grand crus. Margaret Rand meets a few of the family.

Hugel at a glance

Holdings 30ha of estate vineyards plus grapes bought from another 100ha

Grape varieties Riesling, Pinot Gris, Pinot Blanc, Gewurztraminer, Muscat, Sylvaner, Pinot Noir

Annual production 1 million bottles

Key personnel Marc Hugel, winemaker; Etienne Hugel, sales and exports; Jean Philippe Hugel, CEO

Exports 90% of production Wines produced Classic (including Gentil), Tradition, Jubilee, Vendange Tardive, Sélection de Grains Nobles; new Schoelhammer

Hugel Schoelhammer: The first three vintages compared

It is said – usually by the producers themselves – that there are Catholic and Protestant wines in Alsace. The former are more oxidative, forward and ebullient; the latter more reductive, austere and slower to reveal themselves. Riquewihr is a largely Protestant village, and the Hugels of Riquewihr are Lutheran. So there you have it, the style in a nutshell: Hugel wines are tight, structured, mineral and dry – unless they’re sweet.

The last point sounds obvious until you remember that for years now, Alsace sweetness levels have been rising faster than Greek borrowing. Thirty years ago, says winemaker and viticulturist Marc Hugel, the problem in Alsace was getting ripe grapes. Now the issue is avoiding overripe ones. Wines that were routinely dry are now regularly off-dry or sweet, and sweet ones are super-sweet.

To insist on dryness for anything not labelled Vendange Tardive (VT) or Sélection de Grains Nobles (SGN) is to swim against the tide. To refuse to put the words ‘Grand Cru’ on the front label when your Jubilee range comes from the grands crus of Schoenenbourg and Sporen – Hugel’s finest estate vineyards, with Jubilee wines only made in the very best vintages – is also to swim against the tide. And the irony is that Johnny Hugel had been in charge of setting the grand cru rules.

Continue reading below

Tasting Hugel’s Rieslings:

Three generations of Hugel. From top left: Etienne, Andre, Jean Philippe, Marc, Jean Frederic & Marc Andre

Johnny Hugel (his name was Jean, but the British trade renamed him) also drafted the guidelines for the 1984 regulations governing VT and SGN; before that, the German designations were used. He was an influential figure in an influential family: the Hugels, like so many wine families in Alsace, arrived during the Thirty Years’ War (1618-48) and have made wine ever since. Johnny ran the company, with his brothers André and Georges, between 1948 and 1997, when the next generation came to the fore. André still visits the office every day and is a formidable historian of Riquewihr. His mission now is to obtain fair treatment for Alsace veterans of the Second World War, who were conscripted into the German army and receive no pensions.

Johnny tramped all over Alsace with a geologist for three years, examining where the grand cru boundaries should go. ‘If the classification had been honest,’ reflects André’s son Marc, ‘it would have taken one minute, because everyone knew where the boundaries should have been.’ Instead, they were drawn generously. ‘There should probably be 20 grands crus, and the rest should be premier cru,’ says Marc’s nephew Jean Frédéric. So Hugel, having been instrumental in setting up the classification, walked away from it. Trimbach did the same; so did Léon Beyer. No Hugel wine has ever been declared as grand cru, even though many could have been.

The trouble with making a high-minded decision is that the rest of the world goes on without you. Everyone agrees the Alsace Grand Cru classification is not all it should be; but at the same time, most people accept that, overall, it has been a good thing. The decision to boycott it is clearly a difficult one to rethink, yet one wonders how much it benefits Hugel these days. In some Alsace tastings, its flagship Jubilee wines will be ranged with basic Alsace – and that is not necessarily an advantage, given that the former are tight and reticent, and the latter mostly off-dry and come-hitherish. And so Hugel’s grand cru position is under discussion.

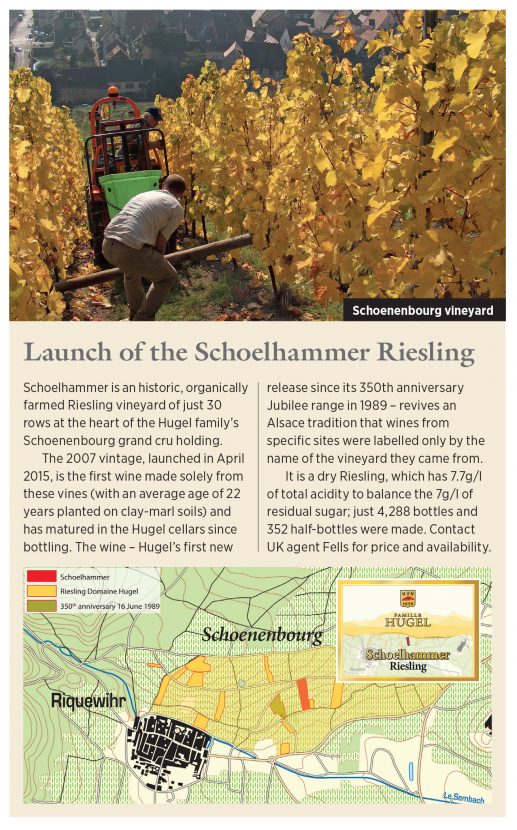

There is something else: the best parcel of Riesling in Hugel’s Schoenenbourg holding has just been released, in April 2015, as a separate bottling called Schoelhammer. The first vintage will be 2007, which neatly gets around the grand cru problem, because if you want to declare a grand cru, you must apply to do so before the vintage. So it won’t be. But it is splendid.

What makes it so good? Tension, in a word. If you want another word, minerality. Schoenenbourg is impressive to look at – it rises steeply from just outside the old walls of Riquewihr – but it’s not homogeneous. Schoelhammer is a perfect kernel of 30 south-facing rows mid-slope, and it was the first Hugel parcel to go organic. ‘It’s clear to the taste when a wine is terroir-driven or varietal,’ says Etienne; and it’s clear here.

The world moves on. They’re all keen to stress that they’re not averse to change; it’s just that they like to do things gradually – change the details rather than take U-turns. The Jubilee range, named to mark the company’s 350th year in 1989, is being renamed because few people know what it refers to; each wine will now have a separate name.

Does this, along with the Schoelhammer launch, constitute a grand cru coming-out? ‘It’s a terroir coming-out,’ says Jean Frédéric. They’re going to make more of a fuss about their undoubtedly excellent vineyards. And Marc is the person to talk to about these: geology has become a passion of his. Did you know that the old vineyard roads in Alsace follow geological fault lines? There are umpteen faults running southwest to northeast, with other, transverse faults running across them. It’s as complicated as the Côte d’Or, which explains why the soils are so many, and so varied.

Obsession with precision

Marc’s winemaking style has evolved over the years. He loves finesse and elegance, and he doesn’t want the mechanics of winemaking to show in the wines, but in 2007 he started doing a little battonage (lees stirring) – not much, and only when it suits the year – just to open up the wines. And he wants absolute accuracy in everything. When he picks for SGN these days, it’s individual berries, not whole clusters. ‘The first 15 minutes of picking [for SGN] are the most important,’ he emphasises, for pinpoint accuracy and purity in the final wine. ‘If you want the best possible wine, you have to be incredibly precise.’

Sweet wines – VT and SGN, and especially the former – are flagships for Hugel. ‘Gewurztraminer VT is 90% of our sweet wine production,’ says Etienne, Jean Frédéric’s father. ‘People confuse sweet wines with dessert wines; it goes beyond pairing them with dessert.’

But the same climate change that has made the general run of Alsace wine sweeter than it used to be has made VT and SGN less exceptional. When Jean Frédéric lists great sweet-wine vintages, he names 1989, 1997, 2000 – then 2005, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2011. Yes, they are more selective than ever, make less per year than they used to, and, says Etienne, sweet wine is still only 2% of their production, but still. Great sweet wine is no longer a rarity in the world – and world demand has not risen. ‘We sell all we produce,’ says Etienne, but one might surmise that shouting a bit louder about the rest of the range might not be a bad thing.

The world moves on. If Schoelhammer is the future, then it works.

Margaret Rand was the 2013 Louis Roederer Feature Writer of the Year for her articles in Decanter